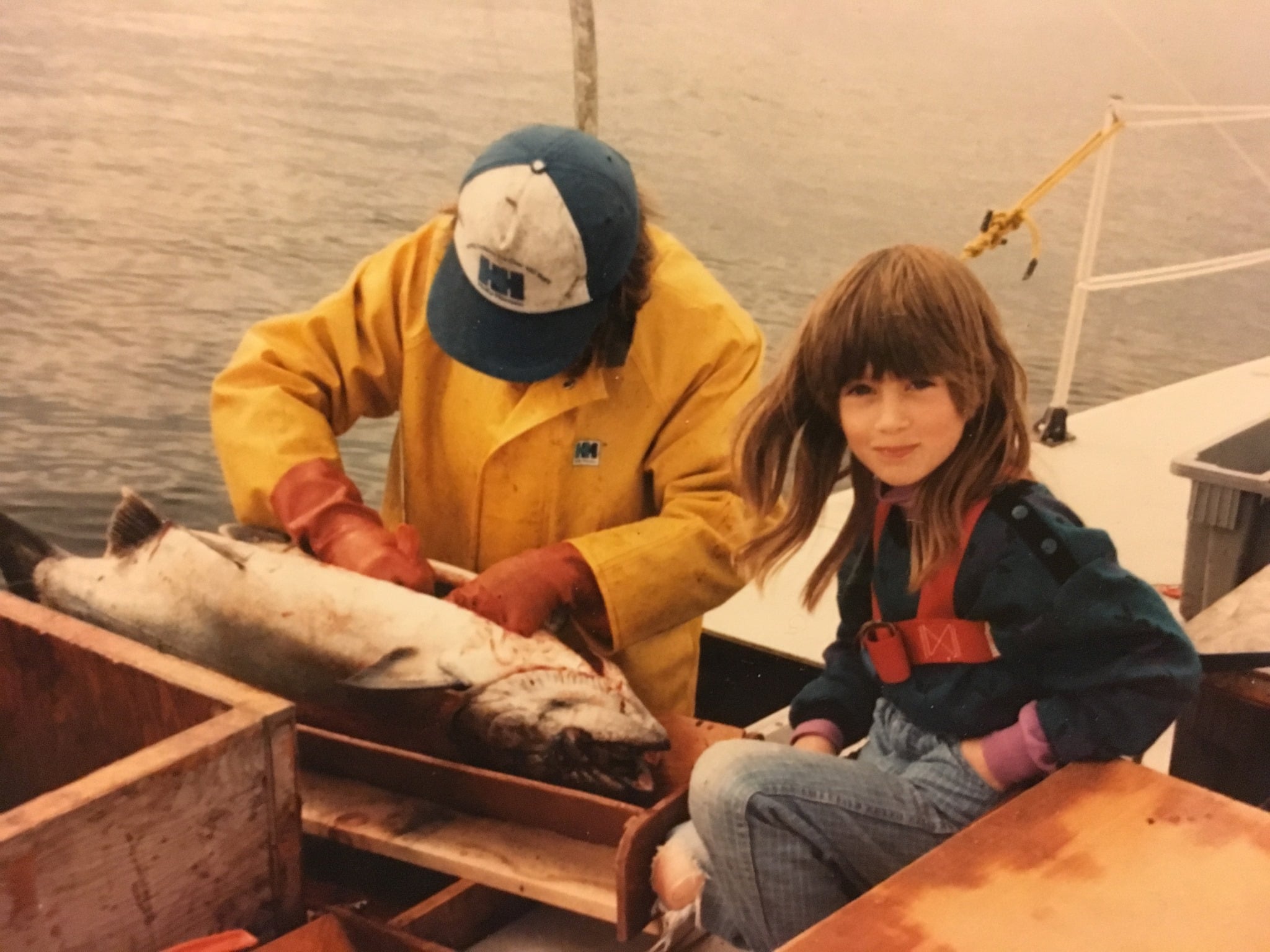

Tele Aadsen has spent nearly her entire life navigating the waters of the Northwest. From the moment her parents built and launched a fishing boat in the 1980s, rhythms of the sea defined Tele’s summers. Fishing taught her about patience, independence, and resilience and planted seeds for a lifelong love of writing and storytelling.

Writing and Fishing

During the short 82-day summer fishing season, Tele watches her lines and the water. She looks for the tug of salmon on the line and for inspiration for her next essay. “It goes back to being that weird little kid, a lonely only child. Reading and writing were my earliest companions,” said Tele.

During the frantic fishing season, finding time to write is a challenge, so she notes her observations from the deck in a notebook on the galley table for later development.

Writing and fishing has become a yearly cycle for Tele, partly due to the annual FisherPoets Gathering in Astoria, Oregon, where fisher-folk share their stories and poems. The gathering each February connects fishers with themselves and with each other. “I can definitely look back at the last 13 years of FisherPoets essays and see themes of what I was really tussling with at the time,” said Tele.

FisherPoets also offers an opportunity for fisher-folk to share their experiences with a wider audience. Tele believes that writing and art can be a bridge between maritime communities and their “land friends.” “That’s one of the values of FisherPoets…so that people really do have a level of connection to their food and their harvesters that is not otherwise available.”

The Fishing Season

Tele’s boat is a troller, which means that they drag fishing hooks on lines behind the boat, catching only a few fish at a time. She describes the process as “beautifully inefficient” and outlines the care that each individual fish receives as they pull them aboard for cleaning and flash-freezing to -40° Fahrenheit. They’ll be shipped, stored, and sold later in the year.

Tele and her partner Joel grew up on their parents’ boats, and Joel’s family passed their boat, the Nerka, to them. But for those without industry connections, breaking into fishing can be difficult. For the past two years, Tele and Joel have brought on a third crew member to assist them and learn their trade. “I have huge respect for the people who are starting from scratch,” said Tele.

Tele’s experience with the challenges of earning a living through fishing is personal. Her parents had difficulty staying in the industry and eventually left.

Commercial fishing operates on narrow margins, and the fishing season depends on rules and environmental factors. Success isn’t guaranteed, and Tele knows that the right relationships and industry knowledge are key to navigating the unpredictable challenges of fishing.

“[Joel and I] are now an example of what my parents had hoped to do but weren’t able to have. We are making a life as salmon trollers, and that’s an enormous gift, and it’s one element of what keeps me coming back,” said Tele.

Fish with a Story

Tele wants people to understand that “there is always cheaper fish available, or fish without a story.” She recognizes that it can be a challenge for consumers to understand where their fish comes from, what the sustainability practices of a given fishery are, and even when in the season the fish was caught. Tele urges customers to develop relationships with fishers to help answer those questions.

“We talk about commercial fisheries as if it’s just one thing…[But] there’s so many different gear types, there’s so many different sizes of boats, and regions, and cultures within each different type of fishery,” she said.

Tele shared that the different types of fisheries tended to attract different people. She and Joel love troll fishing because they can give fish a greater portion of their attention. She also recognizes that she is successful in part because of her network of peers.

“Fisher folks are an interesting mix of super independent, self-reliant personalities who are also a collective,” said Tele. That interdependence showed in last year’s fishing season, when the jellyfish were so dense in the water that, at times, she was unable to catch anything.

“There were entire swaths of the Southeast Alaska coastline of traditional trolling grounds that were absolutely unfishable. You would put your lines down, [and] your hooks would immediately be snotted over with red stinging jellyfish,” said Tele.

Having the support of a network of fishers helped them find the emptier spaces of sea to fish, enabling them to catch enough to support their business.

Mentoring Future Fisherpoets

The interdependence in the fishing community is a central reason Tele and Joel took on a deckhand. While they had once valued their self-reliance, they have also come to see mentoring as an essential part of their work.

Tele pointed out that the common advice for people interested in commercial fishing is to “walk the docks” asking for work. But for young people entering the industry without connections, “the [captain] who needs crew and is going to take this person they just met is probably somebody who doesn’t have a reliable crew for a reason.”

After fishing with her partner aboard the Nerka for 20 years, Tele’s fishing seasons these days are “very different experience from the 19- or 20-year-old who was hopping on other boats where I didn’t feel valued or necessarily safe in an emotional sense.”

Tele fished with her parents as a child, then aboard other vessels during summers in college. After earning her master’s degree, she worked in social work for six years before returning to the water in her late twenties. She hopes that her boat can be a safer place for other young women to come into the industry than what she experienced during colleg

“We’ve got another young woman lined up for this season who’s brand new to fishing and the ocean, and as long as she doesn’t get seasick, I think she’s going to be a rock star,” said Tele.

Tele’s work on the water and with words reflects a deep commitment to community, sustainability, and storytelling. In a world where food sources are often distant and disconnected from consumers, her writing and mentorship bridge the gap between people, harvesters, and the ocean that sustains them.

An excerpt from “What Water Holds” by Tele Aadsen:

The VHF was lively then. Nine years old and perched on the pilot seat, my hand was always poised to switch over, follow verbal breadcrumbs from channel sixteen to six-eight, six-nine. Trolling was a self-professed gentlemen’s fishery, and the radio was my finishing school for the tennis-volley of conversation. To acknowledge your partner’s comment, then lob a return query back. The value of being self-deprecating, quick to deflect compliments while building others up – nothing too over the top, don’t make anyone uncomfortable, but encouraging.

“Nothing goin’ on over here. I can’t catch my ass with both hands today.”

“Ah, you’ll make a day of it, you always do.”

I absorbed fleet norms and etiquette among the dropped consonants and cadence, identifying partner boats and striving to crack their secret codes. “We’ve got a purple apple over here.” “You’re smokin’ us, we’ve only had a blue banana all morning.” I tuned my ears to hear what they said in everything they didn’t. The balance of being able to whine for days, with an underlying optimism that kept their hooks in the water. The artistry of casual, unself-conscious profanity. I aspired to mimic the exact weary intonation of a perfectly groaned “Christ on toast.”