By Vanessa Chin, Maritime Washington Storytelling Intern

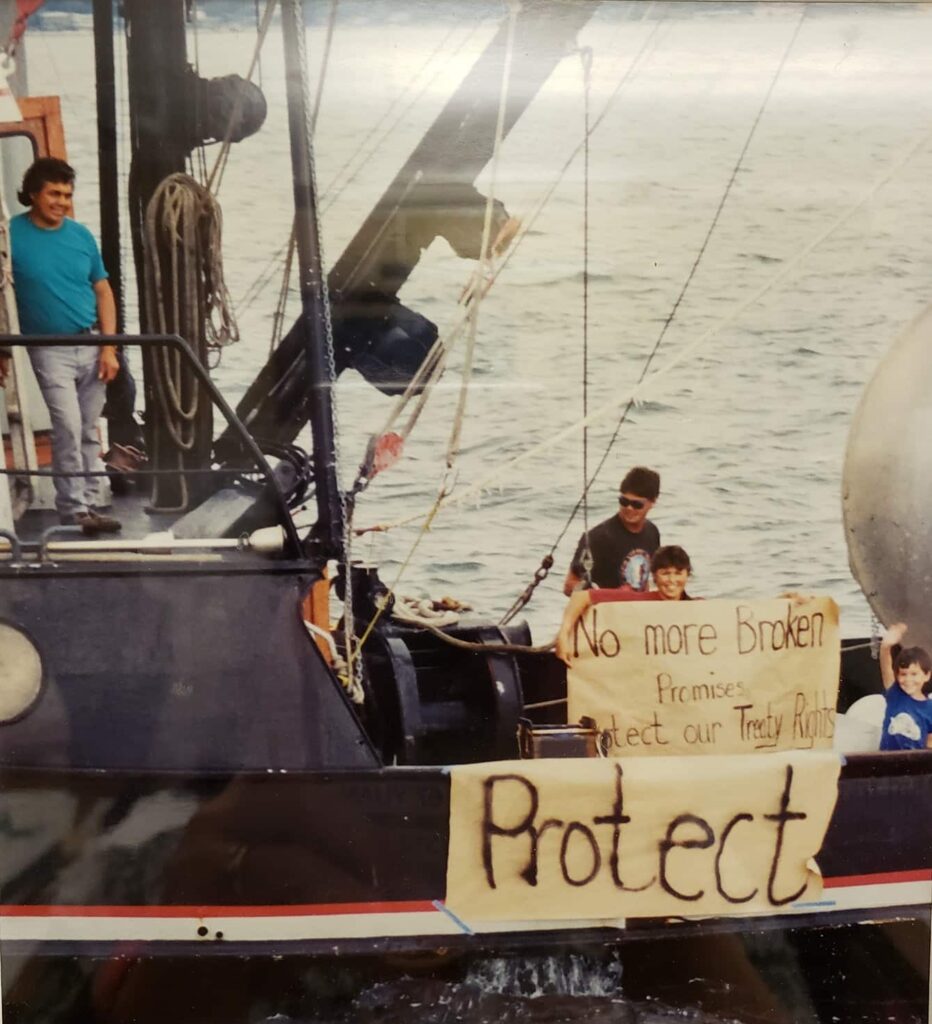

Image above: Ellie’s family seiner, the F/V Salish Sea. All images in this article courtesy of Ellie Kinley.

“Just about everything I ever fought for, you got to tell the story. You got to talk to people, because you never know what one person is going to be the person that can make a difference in the end.”

Tah-Mahs Ellie Kinley, Lummi Nation Fisher and Conservation Advocate

Ellie Kinley went through high school knowing that she never wanted a career that involved public speaking. Decades later, she has become a major voice for Tribal fishermen and for the protection of the Salish Sea.

While Ellie comes from a long line of Tribal fishermen, she only started fishing commercially in her early 20s. “It wasn’t a traditional role, females on the boat,” remarks Ellie. Yet, when she was working 17 hours a day for seven days a week in a cannery in King Cove, Alaska, her dad proclaimed, “If you want to work this hard, you [can] probably do that on my boat.” So the following year, at the age of 23, Ellie went to work for her dad. She’s been fishing ever since.

Members of the Lummi Nation often call themselves the Salmon People. Since time immemorial, salmon have been integral to Lummi traditions and ways of life. However, within one generation, access to that salmon has changed drastically, due to natural disasters, fish farms, and other factors affecting the salmon population. “When I started fishing, we were probably doing it for five, six weeks out of the summer. [Now] we’re down to two and a half days,” Ellie says about fishing for pink salmon. Ellie and her two adult sons can only fish for sockeye salmon once every four years, so they fill in the gap with crabs, prawns, halibut, and low-value chum, but even those permits are limited to a handful of days or even hours. “It’s all very limited nowadays because it’s all by quota, and you only get quota when you have surplus,” explains Ellie. Seeing the effects of these shortages on her community of Tribal fishermen prompted Ellie to become their much-needed voice, she says, because “in order to protect what we have always done, at times, you’ve got to speak about it.”

Like fishing, being a protector also runs in Ellie’s family. Growing up, she watched her dad participate in protests and her aunt protect Tribal village sites, such as Madrona Point on Orcas Island, from development. So when the proposal came through in 2011 to build a coal terminal at Cherry Point, a Lummi Nation ancestral village and reef net fishing site, Ellie knew it was her time to step up and join the fight. That’s when she went to work for Lummi Nation’s Sovereignty Treaty Protection Office.

Numerous local residents and organizations banded together to protest the proposed coal terminal, but it was the Lummi Nation’s petition to the Army Corps of Engineers that led to the project’s shutdown in 2016. Lummi Nation successfully argued that the project would have substantial impacts on their treaty rights to continue to fish in their usual and accustomed areas. “In stopping the coal terminal, that just protected the Salish Sea from becoming more of just a freeway, which then protects the way of life that I know,” says Ellie about one of her proudest accomplishments.

Among Ellie’s greatest achievements has also been her work as a founding member of the Working Waterfront Coalition of Whatcom County and organizer of Bellingham SeaFeast. Ellie says that “SeaFeast has been a joy of my life, to be able to let Whatcom County know what we do in Bellingham for a living, [because] if you don’t even know you have a working waterfront, how do you know that there’s something there that needs to be protected? So much of what we do is simply telling the story. The more you can tell the story, the more people learn, and the more they can realize. People have to realize that every single one of us has a part in what happens to the Salish Sea. We can all do something to protect it.”

Another organization close to Ellie’s heart is the Sacred Lands Conservancy, which was initially founded by her husband Larry and Dr. Kurt Russo as a way for the Lummi Nation to accept land donations. Currently doing business as Sacred Sea, their mission has shifted to protecting and revitalizing the Salish Sea and its inhabitants. One of the efforts at the forefront of Sacred Sea’s work has been the return of Southern Resident Killer Whale Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut, also known as Tokitae or Lolita, back to the Puget Sound after being held in captivity in Miami for more than 50 years. After several years of heartbreaking work and dedication, it was finally announced on March 30, 2023, that Miami Seaquarium would begin the process of returning Tokitae home.

[Editor’s note: Tragically, Sk’aliCh’elh-tenaut died in Miami on August 18, 2023 before she could be transported back to the Salish Sea. The following month, Ellie, along with other members of Lummi Nation, was able to lovingly return her ashes to the sea. “She is home in the Salish Sea,” says Ellie. “She is free.”]

Reflecting back on her conservation work and how others can help, Ellie says, “I think everybody needs to find a way to find the fulfillment you get when you realize you’ve done something good. Even if that, to me, is recycling all your plastic. Recycling your glass. Find something that makes you feel good. And eventually, maybe we can turn things around.”

Listen to an audio adaption of this story, produced by Autio.