Michele Allen, first relief chief mate, stands at the helm of the ferry Salish. She guides her ship into dock and signals her team of crew members to change radio protocols as they begin guiding passengers on board the ferry. Once the vessel is loaded, Michele passes control of the vessel to the other pilothouse. As she steps away from the controls, the small handles that control the massive vessel start moving in mirror to the motions of the captain at the other end of the ship, and the ferry pulls away from the dock.

Today, Michele is piloting the ferry Salish between Fauntleroy and Vashon Island. It’s a “ghost boat” route, which is not publicly announced. It’s just one route in the Washington State ferry system which overall encompasses 10 routes, 21 vessels, and 18.7 million annual riders. The Fauntleroy/Vashon/Southworth route is particularly complicated due to its three ports. Most routes go from one terminal to another without turning, but the “Triangle Route” gets to make a turn at Vashon to continue the journey. “I love doing that. It’s so much fun,” Michele says.

Extensive Knowledge

As first relief chief mate, Michele gets first pick of the available runs, and in the downtime between each 30-minute return journey, she handles paperwork and manages entry-level crew, or OS (Ordinary Seamen). Mates are the second-in-charge of a ferry and take on many of the same duties as a captain, including “piloting,” or driving the vessel. Being first relief means that she is one of the highest seniority mates in the whole ferry system, and she oversees the “relief” runs that take up the slack in the ferry system. For times when other mates have scheduled time off or a route needs extra runs, Washington State Ferries will call in a relief crew and vessel.

Her rank and qualifications mean that Michele needs to know the whole system of routes in detail, rather than just a particular few. Each route “chart” means taking an exam about the details and complexity of each landing site, from planned vessel speeds at different stages of the journey to hidden obstructions and loading procedures for different conditions. Each mate also must hold a first-class pilot’s license and complete 12 round trips (four at night) on each route to even be tested for certification.

Some of that incredible amount of knowledge is on-the-job training, as Michele demonstrates to a younger crew member who joins the pilothouse for one run. The younger woman has never piloted this boat before but has run the similarly-classed ferry Chetzemoka. However, the controls are different on the Salish, and Michele guides her through the differences.

Experience and Training

“Coming up through the hawespipe” is not uncommon in maritime fields, and that tradition is alive and well at Washington State Ferries. Michele had worked aboard fishing vessels in Alaska before coming to Washington State Ferries in 1993. Fifteen years later, she reached her current rank of chief mate.

Michele is relaxed at the controls of the Salish. While it’s one of her favorite vessels, it isn’t her absolute favorite. That honor goes to the Walla Walla, a ferry nearly twice the size of the Salish that is typically assigned to the Bremerton to Seattle route. “That’s the one boat I want to make a landing on my last day, because that’s the first I ever landed,” says Michele.

The Walla Walla was built in 1973. When vessels reach 50 years of service, they get a gold ring painted on their center stack. “We call it the 50-year ring of death, because they usually decommission the boats shortly after that,” says Michele.

Michele hopes to beat the Walla Walla to retirement in the next year and a half. She plans to escape the chilly Washington winters in a warmer climate “like Costa Rica or something like that!” The pilothouse is warm from the unexpectedly sunny day, but the space heater tucked neatly under a table tells of colder days.

Adapting to Conditions

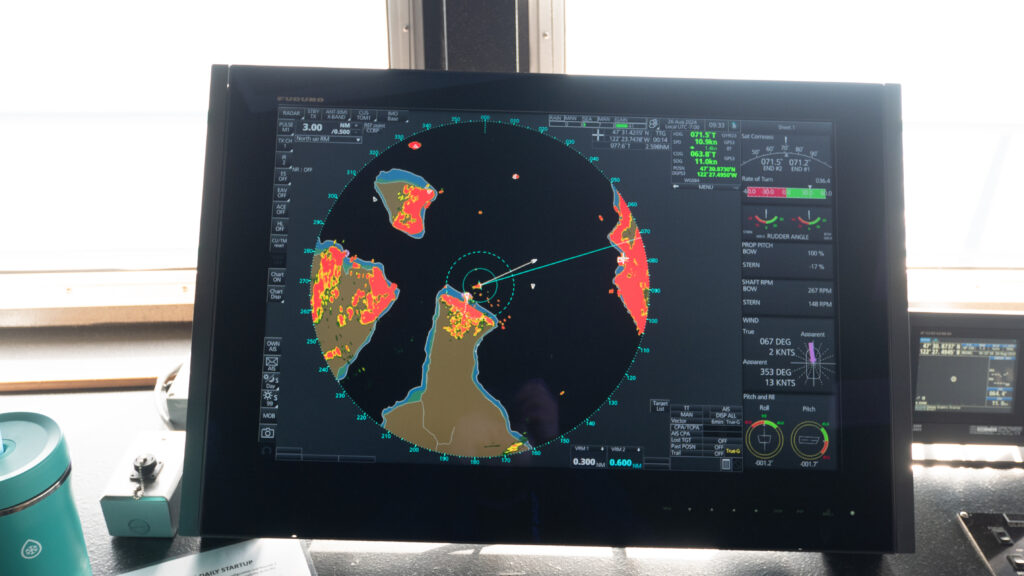

Planning for those cloudier days, two large radar screens display land, boats, debris, and nets. On days with heavy weather, the radar can even pick up storm clouds and show inclement weather approaching, notes Michele. “I run [the radar] the same way as if I can’t see,” she says, despite the clear skies of the day. Other ferries are labeled on the screen, and thin blue lines highlight the location, direction, and speeds of all nearby vessels, buoys, and lanes.

“In Bainbridge, [using radar is] a little bit more critical, because when you’re going around Tyee [shoal] and coming into the channel, you gotta make a turn, and you can’t see where you’re at,” explains Michele as she zooms in to the narrow path between Wing Point and Bill Point on Bainbridge Island.

Michele knows that her level of experience is rare, “so now I just pass on any knowledge I have.” Beyond vessel piloting, she’s even trained crew on everything from payroll systems to internal supply management. For every member of her crew, “you have to be able to tell them how to do their job,” says Michele. “All the policies and procedures, all the maintenance—I’m in charge of all that, because technically the captain shouldn’t have to worry about anything. It’s all on me,” says Michele. “I should be able to tell you how to do it or get you the answer that you need.”

Overcoming Challenges

Maritime careers have traditionally been male-dominated, and Michele has seen plenty of discrimination in her career. She shares stories of times when people in charge either placed her with crews they knew would be chauvinistic or treated her differently because of her gender.

Despite these experiences, Michele remains committed to the maritime industry and to mentoring others. “I didn’t fit the ‘I’m a girl’ persona. When I started here, I embraced everything. I did my job. I tried to do my job as best I could,” says Michele. “If they have a problem with it, it’s usually just because it’s them.”

Michele’s career, marked by adaptability and dedication, will soon transition to retirement. Both of her children have worked for Washington State Ferries, and one is currently working towards an Able-Bodied Seaman (AB) license. For now, Michele continues to pick her favorite routes and impart her knowledge to the next generation.

If you liked this story, you might enjoy other stories about Women on Washington’s Working Waterfronts. Hear from Deb Dempsey, a maritime legend, who was the first woman in the United States to earn a ship pilot license, or hear from Chief Engineer Beth Adams, who works to keep these impressive vessels floating well past the 50-year ring.