By Dr. Terryl Asla and Kathy Sole, Kingston Historical Society

The north end of the Kitsap Peninsula is home to scenic rural areas, charming small towns, and mile after mile of Washington State shoreline. For the uninitiated, the Kitsap Peninsula juts into the center of Puget Sound, separated from the larger Olympic Peninsula by Hood Canal to the west and Sinclair Inlet to the south. While the entire Kitsap Peninsula has a rich maritime history, the lesser-known stories of North Kitsap may surprise you! Test and expand your knowledge of this beautiful and historic region with the questions below.

What is the difference between a cove, a bay, and a sound?

Some common traits help distinguish these three geological features from one another.

A cove has a narrow entrance and is often shaped like a circle or oval. Coves are ideal for anchoring small boats and for recreational activities like fishing, kayaking, and snorkeling.

A bay is a large body of water partially surrounded by land with a single connection to a major waterway or an even bigger body of water. Bays have wide entrances that allow larger boats and ships to enter and dock.

A sound is a coastal waterway—often an inlet or series of channels—usually connected to a sea or ocean in multiple places.

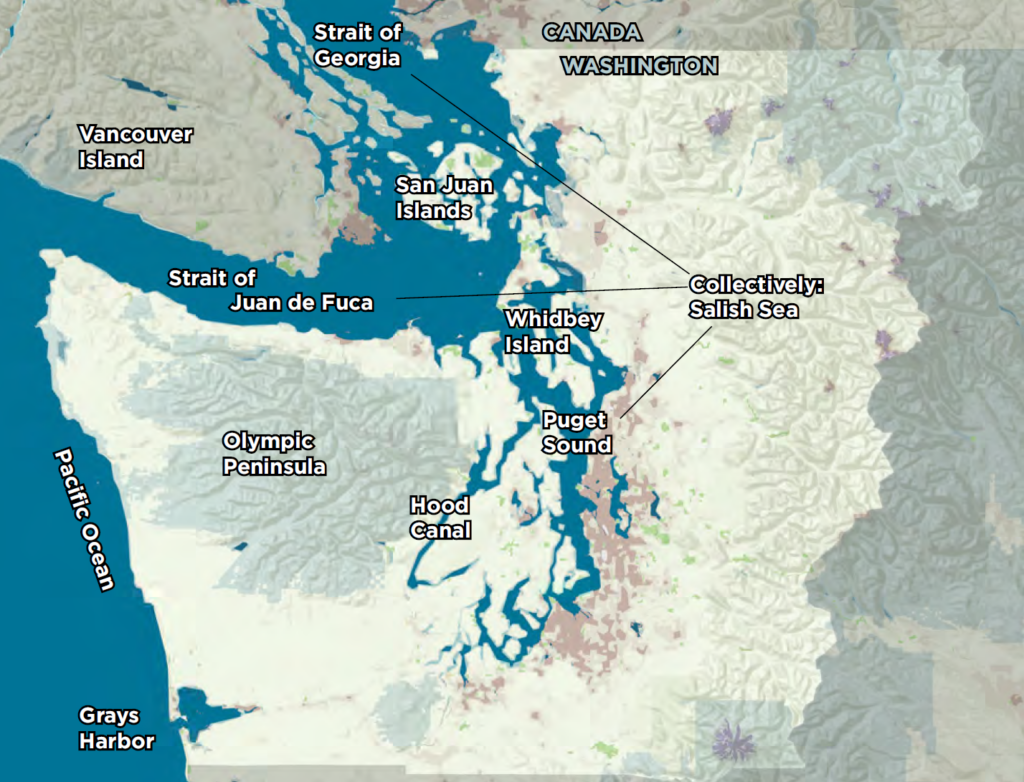

Further Exploration: You can find each of these geological features in North Kitsap! The Washington State Ferry route from Edmonds to Kingston docks at Kingston’s Appletree Cove. Liberty Bay laps at the shores of Poulsbo’s waterfront park, and Port Gamble’s main street overlooks Gamble Bay. And, of course, it’s impossible to avoid Puget Sound, the complex system of salty waterways that extends south from Admiralty Inlet and Deception Pass, including all the waters surrounding the Kitsap Peninsula.

Through an intricate network of channels and adjoining waterways spanning Washington State to British Columbia, Puget Sound connects to the Strait of Juan de Fuca and the Strait of Georgia. The confluence of these and other waterways such as rivers, creeks, lakes, canals, and inlets is known as the Salish Sea, which connects to the Pacific Ocean via the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

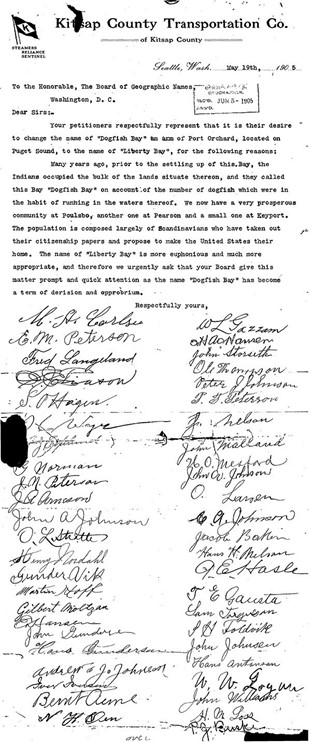

Poulsbo sits on a body of water originally called Dogfish Bay. Why was the name changed to Liberty Bay in 1914?

The inspiration for Liberty Bay may have come from the Frank Johnson family, who emigrated from Sweden to Poulsbo in 1888 and named their homestead and dock Liberty Place. “Fiercely patriotic, the Johnsons were one of the first families on the bay to raise a flagpole and fly the American flag—presumably the one they earned as newly sworn citizens,” according to the Poulsbo Historical Society. “Since their dock was one of the first at the south end of the bay…steamer captains would have become used to referring to it as they entered the bay.” In May 1905, Poulsbo residents petitioned the U.S. Board of Geographic Names to change the name to Liberty Bay. According to the State Committee on Geographic Names, the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, now NOAA’s National Geodetic Survey, officially changed the name from Dogfish Bay to Liberty Bay on November 4, 1914.

Further Exploration: The stories of the people of North Kitsap are some of the most varied in all of Washington. You can find out more about how families like the Johnsons shaped this region by visiting the following museums and their websites:

- In Suquamish, discover the rich heritage of the Indigenous people at the Suquamish Museum and the grave of Chief Sealth (aka Chief Seattle).

- In Poulsbo, visit Poulsbo’s Heritage Museum and the Maritime Museum on Front Street, the Archive and Resource Center at City Hall, and Martinson Cabin on Lindvig Way.

- On Bainbridge Island, tour the Bainbridge History Museum and the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Exclusion Memorial.

- Don’t forget to stop in the quaint town of Port Gamble and enjoy the delightful Port Gamble Museum and the Sea & Shore Museum at Port Gamble General Store.

What do Poulsbo’s Liberty Bay and the story of Pinocchio have in common?

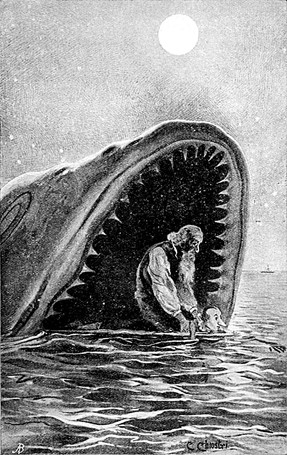

In the 1950 animated film, Pinocchio and his father are swallowed by a whale, but in the original book published in 1883, the finny villain was a monstrous, horrible dogfish that was “bigger than a five-story house with a mouth so big it could swallow a railway train with its smoking engine in a single gulp.” Fortunately, it was a very old dogfish suffering from asthma and a bad heart,. so Pinocchio and his father were able to escape when it snored.

Dogfish—or more accurately, Pacific spiny dogfish—are funny-looking fish that are abundant in Liberty Bay and other waters around North Kitsap. They have huge, protruding, watery blue eyes; a dark brown-to-gray body; a shovel-shaped mouth; and a white, protruding belly that makes it look like it just swallowed a cantaloupe whole.

Ugly appearance aside, dogfish were and continue to be a valuable and useful commodity for the people of North Kitsap. According to Dennis Lewarch, the Suquamish Tribe’s former Historic Preservation Officer, Tribal members traditionally burned dogfish oil for light, used its rough skin for sandpaper, and sold its liver oil to early settlers’ sawmills to help lubricate their machinery.

An earlier version of this story appeared in the North Kitsap Herald.

Further Exploration: Visit Poulsbo’s Liberty Bay and the Suquamish Museum to learn more about how Native people in the area utilized natural resources like dogfish and how those traditions are kept alive today.

How did Appletree Cove in Kingston get its name?

Between 1838 and 1842, the United States commissioned the U.S. Exploring Expedition, also known as the Wilkes Expedition in honor of its commanding officer Lieutenant Charles Wilkes. The goal of the Wilkes Expedition was to explore the Pacific Ocean and survey the surrounding lands. Their journey took them around the world, reaching Puget Sound on their return trip after exploring the coasts of South America, Antarctica, and Australia.

In addition to the Native Americans who had inhabited these lands since time immemorial, many parts of the region were already occupied by Americans who had established forts during earlier expeditions. The U.S. Exploring Expedition stopped at several forts as they journeyed through the Puget Sound, including Fort Nisqually, Fort Clatsop, Fort Vancouver, and others.

In April 1841, expedition leader Charles Wilkes noted in his journal that Appletree Cove was named “from the numbers of that tree which were in blossom around its shores.” Some historians believe Wilkes saw wild crabapple trees in bloom, not apple trees. Other historians think Wilkes observed flowering dogwood trees. We don’t know for certain. But Appletree Cove sounds better than Crabapple Cove or Dogwood Cove, don’t you think?

Further Exploration: Crabapples and flowering dogwoods are significant to the identity of Washington State and to the people of the Suquamish Tribe. They have been signals of the seasons since time immemorial. “Typically, you harvest [cedar bark] when the dogwoods bloom in May and June—when it’s hot but not too hot,” said Marilyn Jones, Suquamish Tribe Traditional Heritage Specialist, in a Northwest Indian Fisheries Commission article. Find more details about the U.S. Exploring Expedition here.

What was the Puget Sound Mosquito Fleet?

Before the region had roads, many private companies ran steamboats that carried passengers and freight to and from the many waterfront docks in Puget Sound and nearby waterways. Collectively called the Puget Sound Mosquito Fleet, the steamboats ranged from 90 to 282 feet in length. The fleet began in the mid-1800s and continued through the 1920s. Eventually, the Washington State ferry system replaced the Puget Sound Mosquito Fleet.

The highways spanning the Kitsap Peninsula wouldn’t be established until 1937. By 1931, a U.S. Postal Service mail truck could travel a dirt road from the Kingston ferry dock to distribute bulk mail to drop-off points in Kitsap County and nearby areas, but getting the mail across Hood Canal was a challenge, as the bridge wouldn’t be built until 1961. A mosquito fleet powerboat pilot known affectionately to the community as Uncle Slug delivered mail to residents across the canal instead. Between 1916 and 1933, the manufacture, sale, and transportation of liquor was prohibited by Washington State and federal law. Unverified rumor has it that Uncle Slug sometimes carried more than just mail in his boat.

Further Exploration: To learn more about the Puget Sound Mosquito Fleet, visit the Kitsap History Museum in Bremerton, where you can see dozens of the boats that made up the fleet in an interactive display and learn which two members of the fleet are still running today!

What was “shooting the tube” in Kingston?

If you travel inland from the marina at Kingston’s Appletree Cove, you’ll find an estuary: a shallow pool created by tides that merges ocean salt water from Puget Sound and fresh water from Carpenter Creek. Beginning in the 1950s, water in this shallow area was carried from one side of the South Kingston Road through a five-foot cement tube called a culvert to the Puget Sound. In the summer, you could ride an incoming tide from Puget Sound through the culvert on a board, small boat, or other homemade floating contraption.

“Shooting the tube” could be a treacherous activity. Longtime Kingston residents reported nearly drowning or having badly cut arms and legs due to barnacles that grew inside the culvert walls. Some water remained in the tube when the tide went out and became stagnant, so the area often smelled bad as well. But “shooting the tube” granted highly-prized bragging rights. Those who succeeded could then run across the road and do it again.

Further Exploration: In 2012, the tiny culvert was replaced by a 90-foot bridge across the waterway to aid the passage of fish. (It smells a lot better now, too!) The bridge was championed by the nonprofit Stillwaters Environmental Center and was a joint project of the Center, Kitsap County, the Suquamish Tribe, and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, with mitigation funds from the U.S. Navy. It is now named the Stillwaters Fish Passage.

What is the origin of the unusual name Point No Point in Hansville?

We have the 1838-1842 U.S. Exploring Expedition to thank or blame once again for this unusual name! Charles Wilkes chose this moniker because the land projecting into the water appeared much less pointed at close range than it did from a distance.

Further Exploration: To learn more about the U.S. Exploring Expedition and Point No Point, visit the Point No Point Lighthouse and Park. The county park and the historic lighthouse are open to the public at certain times during the year. You may even be able to arrange a tour of the oldest lighthouse on Puget Sound or book a vacation rental at the historic Keeper’s Quarters duplex at the Point No Point Light Station.

How has Kitsap County’s coastline been altered over the years?

When you play in Muriel Iverson Park in Poulsbo, attend a free concert at the Mike Wallace Park by the Kingston ferry dock, or visit the Port of Brownsville’s tree-lined park, you’re standing in what was once water. Many of Washington’s public ports owe at least part of their current geography—and a good deal of their dry land—to the efforts of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE).

The USACE is the engineering branch of the United States Army and consists of both civilian and military personnel. Their mission includes civil and military infrastructure projects related to navigable waters, flood control, and our nation’s waters.

Many harbors and waterways in the Maritime Washington National Heritage Area, including those of North Kitsap, have benefited from dredging to remove debris and sediment and to increase the depth of navigation channels, anchorages, and berthing areas for safe passage of boats and ships. The USACE is still working to improve Washington’s harbors.

Further Exploration: At the Port of Brownsville, you can still see the remains of the original coastline. To the west of the main parking lot, look for a tree-lined tidal pool to see where the shore once was.

The Kitsap Peninsula once had two major shipyards. The well-known Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton has operated without interruption as a U.S. Navy facility since it was established in 1891. The second shipyard no longer exists. Where was it located?

Bainbridge Island. If the tide is low at the Bainbridge Island ferry dock, railroad ties leading down the beach into the water may be visible. Those ties are the remains of a marine railway used to move small ships to and from the water in the early 20th century.

Founded in 1903, the company that operated the marine railway was originally called Hall Brothers Marine Railway & Shipbuilding Company, named in honor of the deceased brother of the owner, Henry Hall. In 1916, Captain James Griffiths purchased the shipyard and renamed it the Winslow Marine Railway & Shipbuilding Company.

The shipyard originally built lumber schooners and repaired Puget Sound ferries. World War II shifted the focus and scale of Winslow Shipbuilding. Before the war, the shipyard employed 300 people. By January 1943, that number had grown to 2,300. During World War II, Bremerton’s Puget Sound Naval Shipyard repaired major combat ships from the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Fleet. The smaller Winslow shipyard built and repaired the merchant vessels and workboats that were vital to the war effort.

The Winslow shipyard was most famous for its steel minesweepers—small ships that cleared mines from shallow waters ahead of large vessels. According to the shipyard company’s newsletter, between June 1942 and October 1944, the shipyard launched 17 minesweepers. That’s roughly one every two months!

Further Exploration: The Puget Sound Navy Museum in Bremerton is a great place to learn about the wartime work at shipyards across the Puget Sound but especially those in Kitsap County. To learn more about the former Winslow Marine Railway & Shipbuilding Company, you can also check out the book Hall Brothers Shipbuilders by G. M. White.

What area of North Kitsap was envisioned by developers as a major vacation destination to rival Monterey, California?

Kingston. Washington magazine announced in 1890 that in “Kingston, the Monterey of Washington,” a large “ocean wharf” had already been completed and construction was underway to build a large, beautiful hotel. The article compared Appletree Cove to the historic bay of Monterey, California, and predicted that Kingston would one day become more popular as a summer resort than Monterey itself.

With relatively few parks, recreation facilities, and resorts in Washington State at the time, this luxurious new hotel advertised bathing facilities that were “unequaled on the coast” and touted their easy-to-access location as less than a one-hour trip from Seattle or Tacoma, with a planned hourly ferry.

Developers ran “excursion parties” throughout the summer of 1890 to bring potential hotel and small-business investors to the location. However, they failed to generate sufficient interest, and the hotel was never built. Some investors did construct summer cabins on Kingston’s shores for their families to enjoy weekend and vacation getaways. Later, many of these summer residents tore down the cabins and constructed permanent residences in their place. Small businesses sprung up as well, resulting in today’s charming Kingston downtown.

Further Exploration: Explore the “Monterey of Washington” by visiting Kingston’s downtown and Mike Wallace Park, located at the Port of Kingston near the ferry terminal. For more information about the area, explore the visitors’ center at the Greater Kingston Community Chamber of Commerce in person.