Small speedboats transporting illegal booze down from Canada, smashing through the cold, storm-tossed waters of Puget Sound. The cruel sea might sink them and their cargo. If the Coast Guard caught them, they would be arrested and their boat and cargo confiscated. If liquor pirates hijacked them, they might be murdered. These were the shadow boats, and this is the story of the Prohibition rum runners on Puget Sound.

By Dr. Terryl Asla and Kathy Sole, Kingston Historical Society

Image above: Wrecked shadow boat, courtesy of the H. L. Ferguson Museum.

At the end of the 19th century, a growing international movement opposed the sale of “demon rum,” a slang term for liquor. In 1920, the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and the National Prohibition Act went into effect. They outlawed the manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating beverages, including liquor, beer, and wine. But many Americans still wanted to drink.

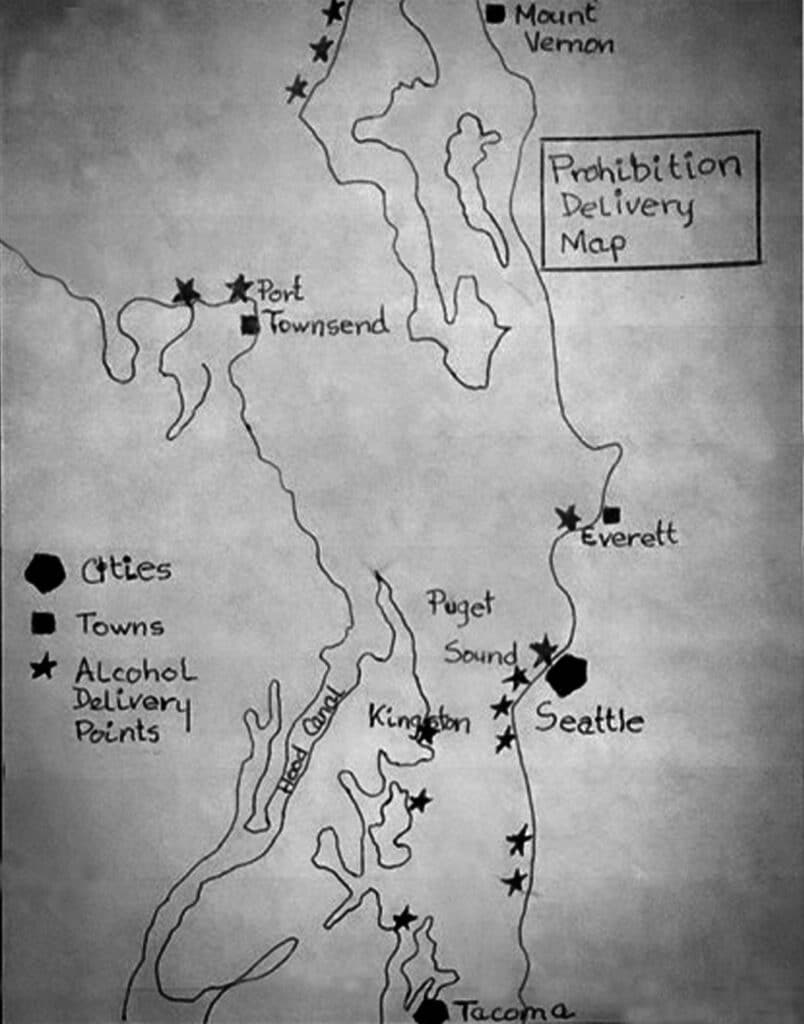

In Washington State, smuggling liquor from Canada by boat offered big money. The waters of the Strait of Juan de Fuca and Puget Sound are generally calmer than the Pacific Ocean, so enterprising private boat owners used vessels of all sizes and types to bring liquor down from British Columbia to Washington’s shores.

Radar hadn’t been invented yet, so traveling by night or in bad weather offered good cover from the Coast Guard and liquor pirates. Because they often traveled at night and without any lights, these rum runners became known as “shadow boats.”

The waters and rocks at the head of Puget Sound—between the northern Kitsap Peninsula and mainland Washington—were particularly dangerous. Kingston residents reported hearing rum runners’ cries for help at night. According to The Kitsap County Historical Society, Kingston resident Ole Hauan reportedly rescued 36 people from boats in trouble during this period.

At first, the Treasury Department was responsible for policing Prohibition at sea. They had few boats, so there was little chance of rum runners being caught, and many believed it was a harmless way to make money.

However, when the U.S. Coast Guard was called in to stop rum runners, the trips became more hazardous. By 1925, the Coast Guard had more than 200 wooden-hulled, 75-foot-long cutters that could do 15 knots and had deck-mounted guns. Many of those boats were built right here in Washington. During Prohibition, Washington boat yards built a fleet of these 75-foot Coast Guard cutters to enforce Prohibition laws farther from shore.

To outwit the Coast Guard, larger mother ships (often schooners) loaded with liquor would anchor far out in international waters outside the territorial 12-mile limit. Then speedy powerboats—often powered by surplus V-12 aircraft engines bought from Boeing—ran the liquor ashore. These smaller craft were called “fire boats” because they carried “firewater.” One particularly speedy style, the “cigarette boat,” had a long, narrow, planing hull, which enabled it to reach high speeds.

To capture these speedy fire boats, the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard in Bremerton built 36-foot patrol boats with speeds of up to 25 knots (29 miles per hour) for the Coast Guard.

Rum running was a dangerous activity. If caught, crew members were subject to arrest, fines, and prison time, and the U.S. Coast Guard confiscated the liquor and seized or sank their boats. The Coast Guard often gave chase to suspected runners with guns blazing, so rum runners repeatedly had to repair bullet holes in their boats before the next run.

In the early days, liquor pirates were another deadly threat. However, piracy declined as gangs and organized crime syndicates began cooperating on the liquor trade, dividing up the territories where they would unload their cargoes and making agreements with onshore businesses to receive their wares. Gang leaders have been described as “generally charming…professional mariners and businessmen” who thought of themselves as simply being in the import shipping business.

The “King of the Puget Sound Bootleggers” was Roy Olmstead, according to Seattle newspapers of the time. An ex-police lieutenant in the Seattle Police, he knew which officers could be bribed and how the police operated.

He used state-of-the-art technologies of the day. He even had his own radio station, KFQX, that allegedly sent coded messages to his men. His business grew to be the largest rum-running operation in Seattle, delivering more than 200 cases of liquor to the city daily. He was jailed in 1927.

At the bottom of the liquor delivery chain were people like the Kingston mailman known as “Uncle Slug.” Mail for Kitsap County was delivered by ferry to Kingston, where it was loaded onto Uncle Slug’s mail truck for delivery. As the story goes, mail wasn’t the only thing Uncle Slug delivered: a stash of liquor was often hidden under the mailbags and delivered at the same time.

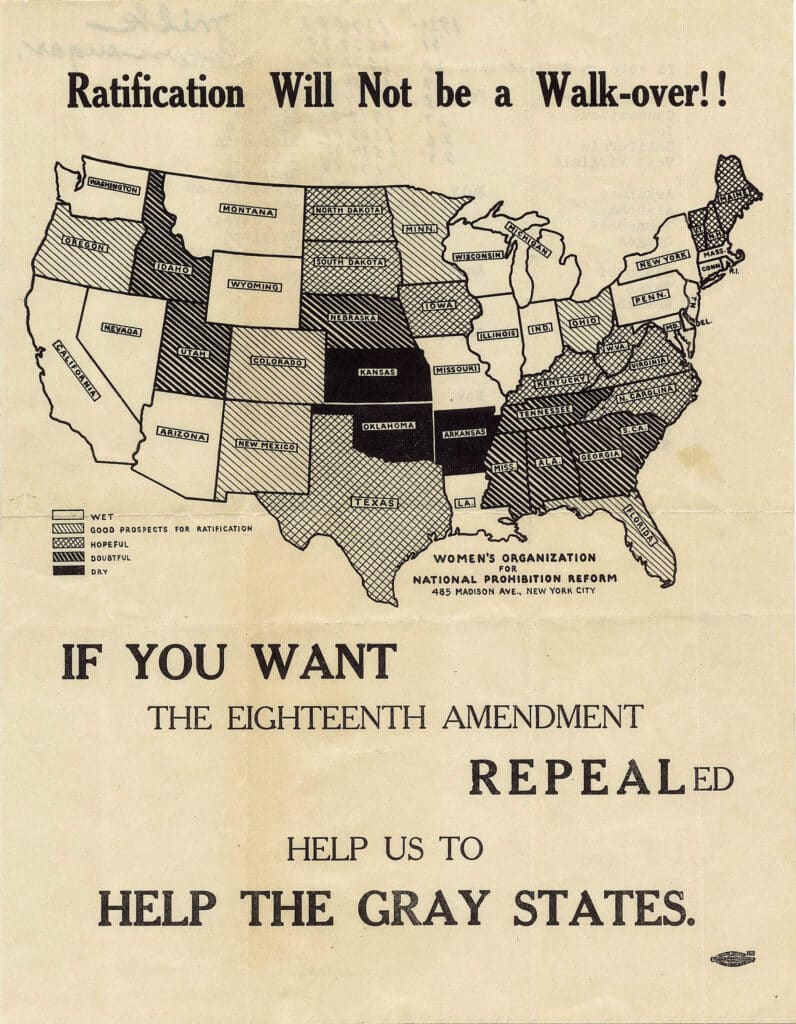

In 1933, Congress passed the 21st Amendment, which repealed the 18th Amendment and ended Prohibition. Thirty-six states had to ratify the amendment for it to take effect. This handbill shows Washington was among the first 19 states to go “wet.”

Afterwards, many rum runners expressed no moral qualms about what they had done. Former Puget Sound rum runner Charles Hudson remarked, “We considered ourselves philanthropists! We supplied good liquor to poor thirsty Americans…and brought prosperity back to the harbor of Vancouver….”

Prohibition lasted 13 years, from 1920 to 1933. Throughout those years, rum runners joined a long line of travelers across Washington’s water highways—ensuring that our shores remained “wet” in more ways than one!

Authors Dr. Terryl Asla and Kathy Sole are published authors and members of the Kingston Historical Society.

Explore More

Online

“1924: Rum Runners to the Gallows.” Saltwater People Historical Society.

Becker, Paula. “Prohibition in Washington State.” Nov 20, 2010. HistoryLink.org.

Dougherty, Phil. “Pomeroy Voters Outlaw the Sale of Liquor on November 5, 1912.” HistoryLink.org.

McShane, Dan. “San Juan Island Rum Runner.” Reading the Washington Landscape.

“Prohibition.” Washington State Historical Society. [Search “Collections” for “Prohibition”]

Williams, Arthur. “Piracy, Murder in Rum Runners Row.” Prince George Citizen.

Books

Funderburg, J. Anne. Rumrunners: Liquor Smugglers on America’s Coasts, 1920-1933. McFarland, 2016.

Mole, Rich. Rum-Runners and Renegades: Whisky Wars of the Pacific Northwest, 1917-2012. Victoria: Heritage, 2013.

Moore, Stephen T. Bootleggers and Borders: The Paradox of Prohibition on a Canada-U.S. Borderland. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 2014.