Story and Photography: Abby Inpanbutr

This article is part of a series highlighting the vibrant people and industries that make up the working waterfronts of the Maritime Washington National Heritage Area. Dive into more stories from our Working Waterfronts photo series here.

An old wooden boat sits easily in the water. For me, it is difficult not to admire her shape, the graceful curves of her lines, lent to her by the inherent qualities of the material itself: wood, steamed and bent and worried into place by craftsmen of another time. This otherworldly aspect is one of the reasons that we humans find boats, particularly boats made of wood, captivating to the imagination. Seeing a beautiful boat, we readily commend the skills of the shipwright or naval architect. But the success of a vessel truly depends on what is between the slender pieces of fir.

The seams between the planks emphasize the form of the hull, as they slope and rise from one end to the other. Fore to aft, in proper boat-speak. The oldest boats built in Washington State, hewn from the oldest trees, had planks that extended the clear length of the vessel. In the early days of building tall ships in Port Ludlow, Port Gamble, and other shipyards of Puget Sound, such planks could be more than 200 feet long. From the late 1800s up until World War II, these shipyards birthed hundreds upon hundreds of boats, forged from the timbers of Washington’s forests. And all these boats had to float, a feat that could not be accomplished by the properties of wood alone.

Caulking is the ancient and elegant solution to this problem, implemented across cultures and centuries, that fills the gaps between a ship’s wooden planks. Even today, the practice is little changed from traditional ways, even if few professional caulkers remain. I was lucky enough to get to know the last full-time caulker on the Seattle waterfront, an encounter that vastly expanded my understanding of wooden vessels. This caulker knew every nuance of his craft and every boat he worked on completely and intimately. His trouble and burden was to keep those boats dry on the inside. I can confidently tell you that, without the expertise of a caulker, a wooden boat is worthless.

The art of caulking is deceptively simple. Here’s how it works. On a new boat, cotton goes in first, wedged as far back between the planks as it will go. Then, the oakum (oiled and rolled hemp) is folded and hammered into the seam with the horsing iron—a specialized wedge—and then hammered in again for good measure. Finally, the seam is painted and topped with cement. Re-caulking a boat involves the additional steps of removing the old caulking (reefing out) and cleaning.

Even with careful caulking, some water works its way in, because the structure of a wooden boat is never static. The planks move and shift with temperature, humidity, and the pounding waves. But the marriage of wood and the organic material so carefully folded and placed in the gaps creates a boundary strong enough to forge a barrier. It is the physical swelling of these ropes of cotton and hemp that will hold back the greedy sea. Therefore, the skill and attention of a caulker is of utmost importance.

Keeping the water on the outside of the tremendous number of wooden hulls that once crowded Puget Sound was the sole responsibility of an army of caulkers, whose profession and life’s work has mostly disappeared. Throughout the early 1900s, waterfront caulkers had their own union and worked in gangs, going from yard to yard as the jobs and seasons demanded. Within the gangs, alone or working in pairs, they pounded their way up and down the seams of all those boats multiple times, at least five if the boat was new and more if it was old, plugging the voids with humble cotton. Traditionally, caulkers finished each day of work preparing for the next one. They would congregate together in the oakum loft, spending their last hour rolling lengths of cotton and oakum over their knees and spinning tales. The material was rolled just so for each particular application, on each particular boat.

The tools of the caulker’s trade included an incredible selection of hammers, mallets, and irons, each with their own specific shape and purpose. Mallets were usually fashioned of mesquite wood for its lightness, balance, hardness, and uniquely pleasant sound. Caulkers spent nearly all of their workday hammering, listening to the noise of wood pounding on wood, so an agreeable sounding mallet was a necessity. A practiced ear could tell without looking whether the caulker was skilled or not. A gang whose swings fell into their groove could result in an experience truly described as musical.

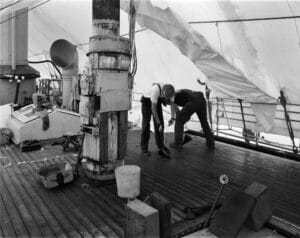

Everything about caulking is methodical. As the seams of a boat are filled in, it becomes solid as the hull is slowly knit together. Finally, on the topside, the spaces between the deck planks are caulked. Over these seams, hot pitch is laid to keep out the rain and waves. On a large vessel, as a team of caulkers works their way across the deck, the boat gradually becomes tighter and more taut, like a giant drum. The hammering changes in tone and frequency as the work progresses inch by inch. At times the vibrations produced are powerful enough to course through the whole body of a ship, shaking through her bones and breaking light bulbs hanging from the beams.

A caulker’s work was simple and focused for days and years on end, a profession I find to be far removed from our fractured and hurried world. But the art of caulking still offers a respite for modern shipwrights, who have described the apparently boring and menial work to me as meditative and thoughtful, albeit a bit tedious. The caulker, one shipwright told me, was like the catcher in baseball, quietly holding the team together and orchestrating the game without drawing much attention—the one to bear the heavy weight of ensuring that the vessel will in fact float once she hits the water. “The caulker covers a myriad of sins,” he said. The work between the seams brings the boat from idea into reality.

Shipyards have been steadily disappearing from Seattle’s waterfront for many years now. But as long as there are wooden boats around, caulking will persist as a necessary skill. Many shipwrights today caulk the boats they work on, with knowledge and respect for the craft that has been passed down to them from the old timers. For many, it remains a place to “fill the well” amidst other complicated work that must be done. There are no more gangs, and the practical music made by a pair of caulkers swinging their mallets is a rare thing these days, but a wooden boat will not last without the continued tradition. So even though the sturdy gangs are gone, to keep the boats afloat, the caulkers’ work must carry on.