By Andrew Weymouth, with special thanks to the Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS)

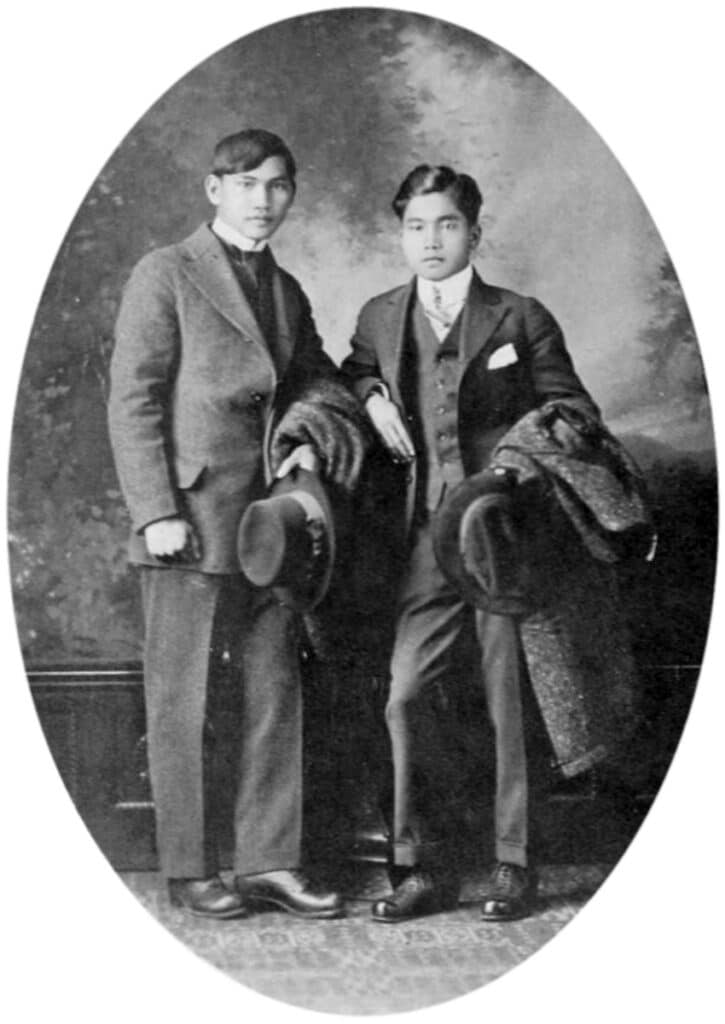

We don’t know much about Salvador Caballero. He arrived in Seattle from the Philippines in September 1917[1] through the Pensionado Act, which allowed Filipino immigrants to enter the U.S. for higher education. Caballero graduated from the University of Washington in 1921, where he was one of 95 members of the Filipino Club.[2]

We know Caballero lived a life connected to the sea, working as a ship steward and a cannery worker in the 1920s. He then moved to California and became a member of San Francisco’s Local 5 chapter of the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packing, and Allied Workers of America (UCAPAWA), eventually becoming its second Vice President in 1939.[3] Caballero appears in newspaper records one last time surviving a shipwreck off the coast of British Columbia, where he was working as a waiter aboard a Navy vessel destined for Ketchikan, Alaska, in 1941.

Although his own records are scarce, Caballero left an incredibly rich and increasingly rare visual document of cannery life in his album of photographs, spanning the 1938-1939 seasons at Larsen Bay on Kodiak Island, Alaska. While there are photographs that document cannery labor that date back to the late 1800s, these were performed by government commissions or industrial manufacturers, often more interested in the machinery and buildings than the workers themselves.[4]

In the 1930s, personal camera technology was becoming more affordable and durable. In this photo, Caballero takes a picture of another worker holding an Anso PD16 Clipper,[5] which retailed for around five dollars at the time.[6] Despite the advances in photography, the migratory nature of cannery work means that not many of these cultural records have been preserved.

Caballero’s photo album was almost lost to history as well, winding up in the attic of Seattle’s Teresa Duran Verfaillie before being donated to Dr. Dorothy Laigo Cordova’s Filipino American National Historical Society (FANHS) archive. Cordova, affectionately known as Auntie Dorothy, guesses that Caballero “must have been a friend of a relative” of Verfaillie, who held on to the album during a period of transition or after his passing. Alongside Dorothy’s late husband, founding president and archivist Fred Cordova, FANHS has worked to “promote understanding, education, enlightenment, appreciation, and enrichment through the identification, gathering, preservation, and dissemination of the history and culture of Filipino Americans in the United States.”[7]

So why did a Seattle student need to travel nearly 1,500 miles to Alaska for work? The answer has both environmental and industrial origins.

The Pacific Northwest had long been home to rich salmon populations, which served as a keystone species for local ecosystems. Before the 19th century, Washington’s waters teemed with five species of Pacific salmon: Chinook, chum, pink, sockeye, and coho. These fish hatched and developed in the area’s abundant freshwater rivers before migrating out to sea to live and grow and then returning home to spawn. These salmon runs have been central to the lives of Native peoples of the Pacific Northwest since time immemorial.

The first West Coast salmon cannery appeared on the Sacramento River in 1864, created by Hapgood, Hume & Company. The science behind canning was so new that owners hid their soldering and cooking techniques from possible competitors in a concealed workspace they dubbed “the bathroom” for the lye baths used in the process.[8] Pollution caused by nearby gold dredging forced the Humes north to the Columbia River, creating the first Washington State canneries in 1866.[9] The Humes were soon followed by competitors who expanded north to Puget Sound, opening facilities in Mukilteo in 1877 (later rebuilt in Seattle), followed by canneries in Tacoma, Blaine, Friday Harbor, Anacortes, Lummi Island, and Point Roberts, a half mile south of the Canadian border.[10]

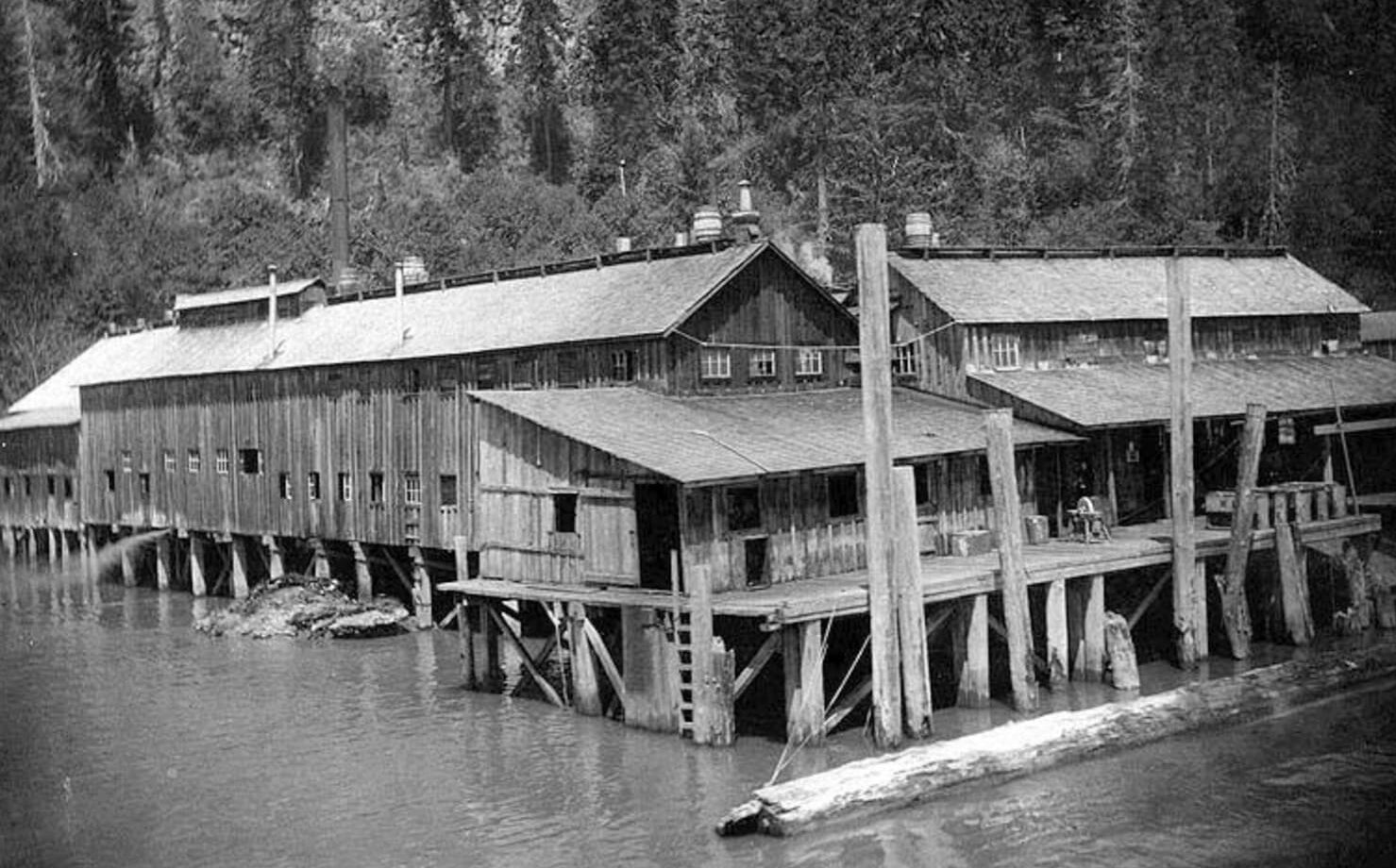

Market expansion and advancement in food canning science in the 1890s led to the formation of the Alaska Packers’ Association, a San Francisco-based syndicate of East Coast financiers. In 1901, the association began taking over Washington-based organizations like the Pacific Packing & Navigation Co., acquiring the canneries at Blaine and Point Roberts and assuming control of the majority of the facilities in Alaska—including the Larsen Bay Cannery documented in Caballero’s photographs.[11]

The Larsen Bay Cannery was located on a four-mile-long inlet on the western shore of Alaska’s Kodiak Island.[12] The cannery’s presence caused a community of multiethnic seasonal workers to cohabitate with an indigenous community that had continually occupied Kodiak Island for at least 2,000 years.[13] When Russian explorers made the first documented contact and established salmon harvesting operations in the late 1700s, they named these people Aleuts (meaning community), now popularly Alutiiq.[14]

There are a number of reasons why Alaska was an attractive resource for powerful organizations. By 1900, the Columbia River was being depleted through overfishing, and the Fraser River’s proximity to the Canadian border made fishing rights and “fish piracy” a constant debate.[15] In contrast, Alaska provided 3,000 islands and 33,000 miles of largely uninhabited coastline, which gave corporations with exclusive access to rich salmon runs and a workforce rendered essentially captive through seclusion.[16]

The expansion of the salmon canning industry in Alaska contributed to the Port of Seattle’s establishment in 1911. By 1915, Alaskan trade made up 15% of Seattle’s total commerce,[17] and by the 1930s, the city was shipping more salmon internationally than every other U.S. port combined.[18] Seattle’s ascent as a port city made it an ideal hub for Filipino cannery workers, known as “Alaskeros,” to rest between migratory circuits along Puyallup hop farms, lumber mills in Grays Harbor, and the canneries of Alaska.[19] Seattle provided a central location where Alaskeros could find temporary housing in the International District, stay informed at the local union hall, and quickly access trains and ships to their next source of income.[20]

Canning seasons were coordinated around the annual salmon spawning period, which can be as short as 15 days but are prepared for as early as June and concluded by August.[21] Positions at the canneries were heavily influenced by both gender and ethnicity. The first wave of Pacific Northwest cannery workers came from China in the 1870s and reached their peak in 1902,[22] followed by Japanese immigrants in the 1910s and Filipinos at their highest percentage in 1930.[23] Fishing positions were generally given to White or European fishermen,[24] while work inside the cannery was usually divided between an indigenous and Asian workforce.[25] Female laborers tended to be given positions as hand labelers and “slimers,” tasked with washing and removing entrails from the salmon.

While there are early accounts of labor contractors recruiting Alaskeros directly from the Philippines or from sugarcane plantations in Hawaii,[26] by the 1920s, most of the enlisting was done in the streets of San Francisco, Portland, and Seattle.[27] In these cities, cannery owners would negotiate with labor contractors for work including transporting salmon from the docks to the canning facility, butchering, packing, cooking, and labeling the fish, before being hauled back to market-bound ships. In turn, labor contractors supplied individual workers with food, lodging, and transportation, in this case on the Alaska Packers’ Association “star fleet,” a group of 30 ships that hauled both workers and cargo along the Pacific.[28]

Conditions on ships to Alaska were often unsanitary, undersupplied, and sometimes indistinguishable from human trafficking. There are accounts of 80 laborers being forced to share one pan of water a day and passengers not being allowed to leave the ship when they were at port, forcing them to purchase food and basic goods from the contractor at dramatically increased prices.[29] Multiple articles describe workers “escaping” intolerable conditions on the ships, often treated with contempt by journalists who slandered the workers for “backing out” of their contracts.[30]

Once at the canneries, working conditions were often not much better. Violence was common and, given the tools of the trade, tended to escalate quickly. In one 1917 incident, a contractor named J.J. Cunningham and the Filipino foreman he hired were both stabbed in a “disagreement” with Filipino cannery workers at Larsen Bay. One of the cannery workers had his mouth “ripped open” by a pair of scissors, and another was stabbed in the foot with a pew. In addition, labor contractors, frequently Japanese, Chinese, or Filipino, often included predatory stipulations in their labor contracts, such as charging laborers for every hour of overtime they refused, for not “treating the Chinese foreman respectfully,” and for smoking “about” the cannery—an offense that could lead to a fine of $50, roughly $1,000 today.[31]

Newspapers as far away as Australia reported on “slavery in Alaska,” specifically highlighting University of Washington students “who spent the summer working in the north.”[32] An account from 1924 emphasized that the escapees aboard a “hell ship” destined for Bristol Bay were graduate students from Seattle.[33] Though equally dangerous conditions existed for previous generations of laborers, the shifting educational demographic of Alaskeros in the 1920s may have changed public sentiment and helped bolster support for unionization.[34]

While there are documented efforts to organize salmon fishing as early as 1867,[35] these efforts made little lasting impact until the 1933 formation of the Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers’ Union (CWFLU) in Seattle. Though it may seem odd for workers to risk organizing during the Great Depression, the lack of positions brought corrupt systems created by labor contractors into sharper relief and rallied Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino interests under the same cause.[36] The Seattle cannery union’s first major success was the abolishment of the exploitative contract labor system in 1935.[37]

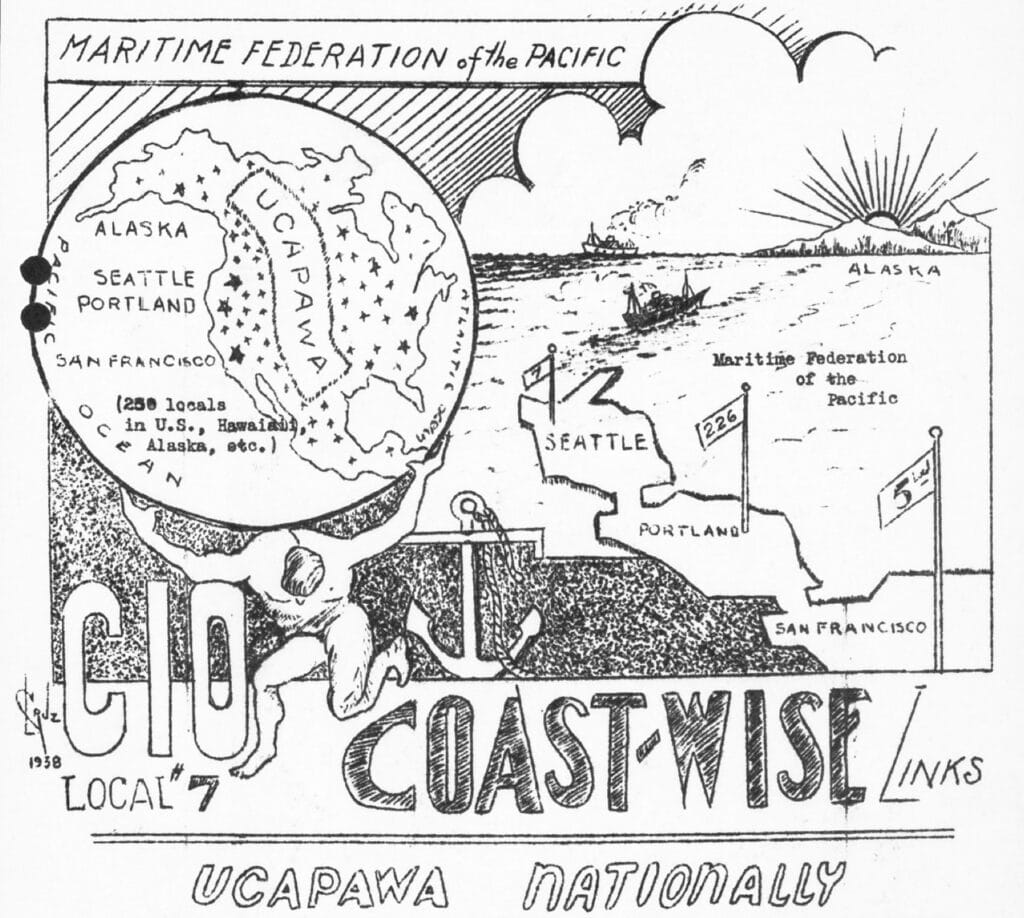

Conditions that had been tolerated by previous generations were being reevaluated and articulately criticized by the founding members of the CWFLU, four of the six of whom were graduate students in Seattle.[38] After a violent succession of leadership, the CWFLU affiliated as UCAPAWA in 1937 and soon established 250 locals (or chapters), including the Local 5 in San Francisco, the 266 in Portland, and the 7 in Seattle, dubbed the “Maritime Federation of the Pacific.”[39]

Though he wasn’t aware of it, Caballero was also documenting the cannery union’s multiethnic vision before it would be permanently altered by World War II. The “race unity” in the headline announcing Caballero’s election in the Local 5, alongside Japanese, Chinese, Mexican, and White union leaders, became an impossibility.[40] The incarceration of Japanese American union members and the conscription of others led to the San Francisco and Portland chapters merging with Seattle’s Local 7 out of fear of dissolution.[41] The war only compounded the dangers described for laborers traveling to and from salmon canneries.

While Caballero’s historical record is obscured after he was shipwrecked in British Columbia, his legacy lives on through his camera. In sharp contrast to photos produced by industrial interests—where Asian and Native American labor is frequently glimpsed as faceless bystanders around towering machinery—Caballero’s album is a truly unique document of cannery workers at a human scale, on their own time and through a Filipino lens.

Listen to an audio adaption of this story, produced by Autio.

[1] Cordova, F., Cordova, D. L., & Acena, A. A. (1983). Filipinos, forgotten Asian Americans: A pictorial essay, 1763-circa 1963. Dubuque, Iowa : Kendall/Hunt Pub. Co. http://archive.org/details/filipinosforgott00cord

[2] University Of Washington. (1891). Tyee 1921 Volume Xxii 05. http://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.168582

[3] Yoneda, K. G. (1983). Ganbatte: Sixty-year struggle of a kibei worker. Los Angeles : Resource Development and Publications, Asian American Studies Center, University of California, Los Angeles. http://archive.org/details/ganbattesixtyyea00yone

[4] Moser, J. F. (1899). The Salmon and Salmon Fisheries of Alaska: Report of the Operations of the United States Fish Commission Steamer Albatross for the Year Ending June 30, 1898. U.S. Government Printing Office.

[5] Agfa Ansco PD16 Clipper. (n.d.). Louisiana Digital Library. Retrieved March 15, 2023, from https://louisianadigitallibrary.org/islandora/object/lsu-sc-furlow:40

[6] The Evening Sun 25 Jun 1938, page Page 5. (n.d.). Newspapers.Com. Retrieved March 23, 2023, from https://www.newspapers.com/image/48347355/

[7] http://fanhs-national.org/filam. (n.d.). About FANHS. FANHS. Retrieved March 14, 2023, from http://fanhs-national.org/filam/about-fanhs/

[8] Carstensen, V. (2021). The Fisherman’s Frontier on the Pacific Coast: The Rise of the Salmon-Canning Industry. In J. G. Clark (Ed.), The Frontier Challenge (pp. 57–80). University Press of Kansas. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1p2gmd5.8

[9] Carstensen, V. (2021).

[10] The development of the Pacific salmon-canning industry: A grown man’s game. (1989). Montréal [Que.] : McGill-Queen’s University Press. http://archive.org/details/developmentofpac0000unse

[11] Salmon Canneries of the Pacific Northwest. (n.d.). [Image]. Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Retrieved March 19, 2023, from https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4232c.mf000036/

[12] CoastView. (2021, July 8). Larsen Bay Cannery, Kodiak Island. CoastView. https://coastview.org/2021/07/08/larsen-bay-cannery-kodiak-island/

[13] Gard, R., & Bottorff, R. L. (2014). A History of Sockeye Salmon Research, Karluk River System, Alaska, 1880-2010. U.S. Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service.

[14] The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire. (n.d.). Retrieved March 12, 2023, from https://www.eki.ee/books/redbook/aleuts.shtml

[15] Wadewitz, L. (2006). Pirates of the Salish Sea: Labor, Mobility, and Environment in the Transnational West. Pacific Historical Review, 75(4), 587–627. https://doi.org/10.1525/phr.2006.75.4.587

[16] Mathieson, R. S. (1954). The Alaskan Salmon Industry—: Prologue and Prospect. Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers, 16(1), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1353/pcg.1954.0000

[17] Gates, C. M. (1948). A Historical Sketch of the Economic Development of Washington since Statehood. The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, 39(3), 214–232. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40486789

[18] Freeman, O. W. (1935). Salmon Industry of the Pacific Coast. Economic Geography, 11(2), 109–129. https://doi.org/10.2307/140157

[19] Roces, M. (2016). “These Guys Came Out Looking Like Movie Actors.” Pacific Historical Review, 85(4), 532–576. https://doi.org/10.1525/phr.2016.85.4.532

[20] History through a Postcolonial Lens: Reframing Philippine Seattle. (2023).

[21] Mathieson, R. S. (1954). The Alaskan Salmon Industry—: Prologue and Prospect. Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers, 16(1), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1353/pcg.1954.0000

[22] Nineteenth-Century Chinese and the Environment of the Pacific Northwest. (2023).

[23] Bulosan, C. (editor). (n.d.). International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union Local 37 yearbook, 1952.

[24] Moser, J. F. (1899). The Salmon and Salmon Fisheries of Alaska: Report of the Operations of the United States Fish Commission Steamer Albatross for the Year Ending June 30, 1898. U.S. Government Printing Office.

[25] Moser, J. F. (1899). The Salmon and Salmon Fisheries of Alaska: Report of the Operations of the United States Fish Commission Steamer Albatross for the Year Ending June 30, 1898. U.S. Government Printing Office.

[26] Humanities, N. E. for the. (1911, May 4). The Fargo forum and daily republican. [Volume] (Fargo, N.D.) 1894-1957, May 04, 1911, Image 7. 1911/05/04. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85042224/1911-05-04/ed-1/seq-7/

[27] Seferovich, G. H., & DeLoach, D. B. (1940). The Salmon Canning Industry. Journal of Marketing, 4(3), 323. https://doi.org/10.2307/1246743

[28] Alaska Packers Association records—Archives West. (n.d.). Retrieved April 22, 2023, from https://archiveswest.orbiscascade.org/ark:80444/xv77299

[29] The Seattle Star 25 Apr 1924, page 9. (n.d.). Newspapers.Com. Retrieved February 26, 2023, from https://www.newspapers.com/image/858028471/

[30] San Francisco Chronicle 18 Apr 1911, page Page 18. (n.d.). Newspapers.Com. Retrieved February 26, 2023, from https://www.newspapers.com/image/27340017/

[31] The Seattle Daily Times 1917-02-27. Retrieved February 26, 2023, from https://aweymo.github.io/CS.2/item.html

[32] SLAVERY IN ALASKA. (1928, January 4). Australian Worker. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article145991908

[33] The Seattle Star 25 Apr 1924, page 9. (n.d.). Newspapers.Com. Retrieved February 26, 2023, from https://www.newspapers.com/image/858028471/

[34] Historical Timeline. (2012, January 18). The Filipino American Experience. https://filipinostudies.wordpress.com/historical-timeline/

[35] Hinnershitz, S. (2013). “We Ask not for Mercy, but for Justice”: The Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers’ Union and Filipino Civil Rights in the United States, 1927-1937. Journal of Social History, 47(1), 132–152. https://doi.org/10.1093/jsh/sht055

[36] Cannery Workers’ and Farm Laborers’ Union 1933-39: Their Strength in Unity—Seattle Civil Rights and Labor History Project. (n.d.). Retrieved March 2, 2023, from https://depts.washington.edu/civilr/cwflu.htm

[37] Seferovich, G. H., & DeLoach, D. B. (1940). The Salmon Canning Industry. Journal of Marketing, 4(3), 323. https://doi.org/10.2307/1246743

[38] Hinnershitz, S. (2013). “We Ask not for Mercy, but for Justice”: The Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers’ Union and Filipino Civil Rights in the United States, 1927-1937. Journal of Social History, 47(1), 132–152. https://doi.org/10.1093/jsh/sht055

[39] Publicity Committee, C. W. and F. L. U. L. 7, UCAPAWA, CIO. (n.d.). Maritime Federation of the Pacific, CIO Links UCAPAWA Nationally. Retrieved March 2, 2023, from https://jstor.org/stable/community.29378774

[40] Dōhō 1939.11.15—Hoji Shinbun Digital Collection. (n.d.). Retrieved March 19, 2023, from https://hojishinbun.hoover.org/?a=d&d=tdo19391115-01.1.4&e=——-en-10–1–img-%22s.+caballero%22+cannery——

[41] Bulosan, C. (editor). (n.d.). International Longshoremen’s and Warehousemen’s Union Local 37 yearbook, 1952. Retrieved March 2, 2023, from https://jstor.org/stable/community.29378671