By Vanessa Chin, Maritime Washington Storytelling Intern

Image above: Photo of Squaxin Island Tribal members clam digging. Courtesy of Squaxin Island Museum.

Since time immemorial, people have both shaped and been shaped by the islands and waterways of Puget Sound. To preserve some of these stories, the Tacoma Community History Project has collected oral history interviews since 1991. Over sixty collections have been produced by University of Washington Tacoma students, featuring a wide range of subjects diverse in both their cultural backgrounds and life experiences. Through this project, people from the South Sound have been able to share their stories about events and forces that have molded their communities and the wider region—including its rich maritime heritage.

A highlight of this collection is Squaxin Island Lives, an oral history project completed by Carrie Bratlie in 1993 that contains recordings and transcripts from interviews with four Squaxin Island Tribe members. James Krise and three generations of the Peters family discuss their life experiences and personal connections to Squaxin Island.

With members spread throughout the South Puget Sound region, the Squaxin Island Tribe has proudly maintained their culture, traditions, and history for thousands of years. After the 1854 signing of the Treaty of Medicine Creek, the indigenous people who lived along the shores and watersheds of the seven southernmost inlets of Puget Sound were assigned reservation land on a small island. The island, located due north of Olympia, was named after the people of Case Inlet and became known as Squaxin Island. Over the years, people gradually left the island to return to their original homes and continue their maritime traditions.

James Krise

Bratlie’s first interview subject, James Krise, was born in 1916 on the Skokomish Indian reservation. His maternal grandfather was John Slocum, founder of the Indian Shaker Church. During the interview, James recounts stories from his youth along the shores of Puget Sound, like digging for clams with his brother Randy. Other stories include running away from an Indian boarding school by hopping on a railroad car, working as an oyster harvester, serving in World War II, and being invited to live on the Apache Reservation in Arizona. Later, James discusses more sensitive topics such as the prejudice and hardships that both himself and the Squaxin Island Tribe have had to overcome.

Josephine Peters

Throughout all four conversations, Bratlie explores the experiences her interviewees have had with prejudice. However, it seems that experiences differ widely between generations of the Peters family. Josephine Peters was born on Squaxin Island in 1904 and fondly remembers her childhood spent playing on the beach, digging up clams, and attending the Shaker Church. When she was in fifth grade, Josephine’s family moved to Lake Cushman, where her father got a job as a logger. The family lived in company housing and Josephine never felt slighted by the community for being Native American.

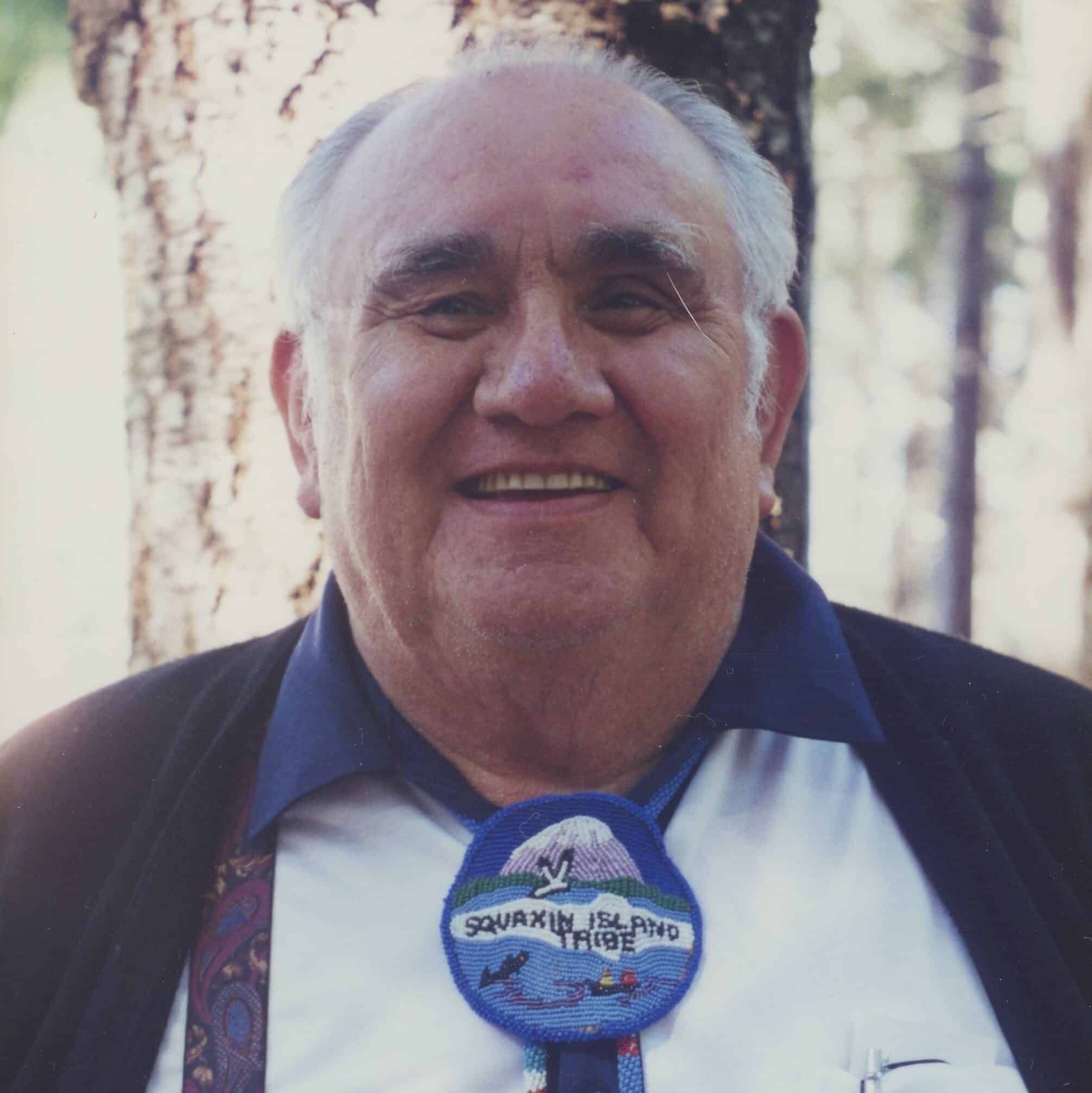

Calvin Peters

This is in sharp contrast to her son, Calvin, who tells Bratlie about a time when he stood up to his classmates’ insults regarding the cleanliness of Indian homes. Calvin grew up on Mud Bay, just outside Olympia, and discusses his regret at not being able to learn his Tribe’s traditional ways of life. However, Calvin did grow up practicing at least two Tribal traditions: fishing and harvesting oysters. Perhaps because of this, he sat on the council that was responsible for bringing forth litigation that would result in the Boldt Decision.

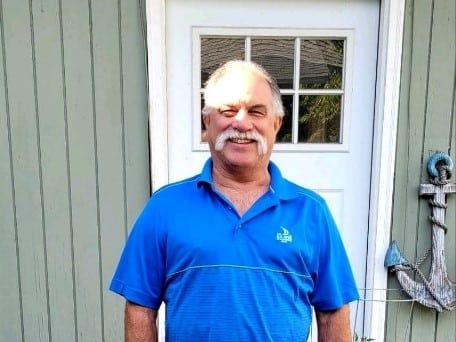

Mark Peters

Calvin’s son, Mark, remembers collecting oysters in his grandfather’s oyster bed on Squaxin Island and doing a lot of pole fishing. Growing up in the Tacoma area in the 1960s and 70s, he remembers people being intrigued about his heritage. However, as he grew up and became a fisherman to earn his income, he encountered hostility from white fishermen, including being shot at multiple times. Despite this, Mark taught his children how to fish and hoped that they would one day learn their native language.