By Vanessa Chin, Maritime Washington Storytelling Intern

Take a short ferry ride west from Seattle into Puget Sound and you’ll find yourself arriving on Bainbridge Island. Part of the traditional lands of the Suquamish Tribe, the island first saw the arrival of white homesteaders in the 1870s. These new arrivals came by boat, quickly clearing sections of land and processing the timber in local sawmills. The mills employed many Japanese immigrants and, after the loggers moved on, some stayed on the island to clear additional trees for farming settlers and to work the land themselves. Farming soon became the island’s main economic driver, and its most notable export was the strawberries grown by Japanese American farmers who would harvest and deliver the fruit by boat to Seattle for canning. Farming on an island meant that Bainbridge locals were heavily dependent on water-based transportation for bringing in supplies and sending their goods to market. From the 1850s through the 1950s, this meant relying on the famous “mosquito fleet”—the hundreds of privately operated boats that transported people and goods across Puget Sound before the development of Washington’s public ferry system.

Thanks to the regional connections provided by the mosquito fleet, berry production boomed and, by 1915, Bainbridge farmers needed more hands to help pick the crops. Although they had previously relied on migrant First Nation harvesters from Canada, the increase in berry farming prompted farmers to hire Filipino workers, some of whom had already come to the island to work in the sawmills and Eagle Harbor’s Hall Brothers Shipyard. These communities—Native, white, Japanese, and Filipino—were all drawn to the shores of Bainbridge Island for its natural resources and opportunities. They taught and helped each other through hardships, including those brought on by the bombing of Pearl Harbor and Franklin Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, which forcibly removed 110,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast, starting with Bainbridge Island.

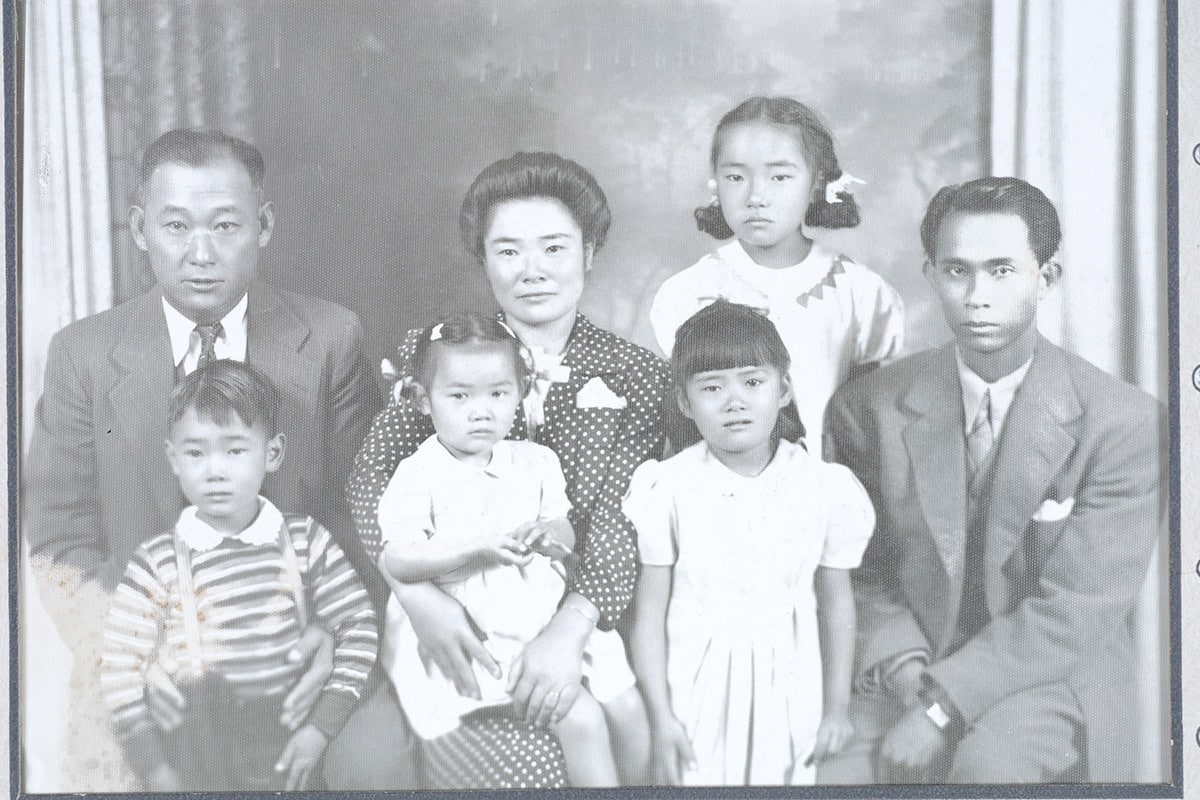

Images above courtesy of the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community. Explore many more historical images and stories on their website.

Dedicated to preserving and sharing stories about the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans, Densho maintains a collection of over 900 oral histories in its Digital Repository. Along with historic photographs, documents, and other primary source materials, these resources tell the story of Japanese Americans from immigration through the World War II incarceration and its aftermath. Housed within this archive is the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community Collection which includes 41 oral histories recorded between 2006 and 2008. Curated selections from this extensive oral history collection can also be found on the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community (BIJAC) website. While several interviews discuss maritime themes, two particularly highlight the unique dynamic that developed between Japanese Americans and Filipinos.

Doreen Rapada was born on Bainbridge Island in 1943. Her father immigrated from the Philippines, and after spending some time working in Alaskan fish canneries, he heard that Japanese American farmers on Bainbridge Island needed workers. He ended up settling on the island, and was taught by the Japanese American farmers how to grow berries and survive by fishing and harvesting shellfish. In 1942, he leased a property from the Furukawa family to start his own farm. That summer he met and married Doreen’s mother, a member of the First Squamish Nation, who traveled from Canada to pick berries. During the war, Doreen’s father continued to farm while also taking shifts at the Hall Brothers Shipyard, before becoming an American citizen and working as welder at the Puget Sound Naval Shipyard. Doreen recounts how her father continued his friendship with Japanese American residents upon their return to the island at the end of the war by sharing the family’s salmon catch and supporting their businesses.

A founder of the Bainbridge Island Japanese American Community organization, Frank Kitamoto was also born on Bainbridge Island and was only three years old when his family was incarcerated at Manzanar and later Minidoka concentration camps. His grandfather purchased a farm on the island in 1917 and sold it to Frank’s parents when he went back to Japan in 1935. Prior to the war, Frank’s mother ran the farm and his father worked as a salesperson for Friedlander’s Jewelry, commuting on the ferry to Seattle nearly every day to sell rings to visiting Japanese sailors. When Frank’s father learned of the pending imprisonment, he signed a contract with Felix Narte—a trusted Filipino friend who had worked on the farm for several years—to look after the farm and share the profits. Frank remembers fondly that, even after the war, the relationship between his family and Felix was special.