By: Cynthia Nims

Oysters have long held a significant place in the culture, economy, and gastronomy of Washington State. For countless generations, oysters have been of great importance to Indigenous populations in this region for sustenance, traditions, and trade. Some European settlers that arrived in the mid-19th century ventured into businesses based on the native oyster, which came to be known as the Olympia oyster. Initially, these enterprises relied simply on harvesting wild oysters from their natural beds. Before long, there began a gradual shift toward cultivation, with initial steps such as plotting out new oyster beds and building dikes to contain water and protect oysters.

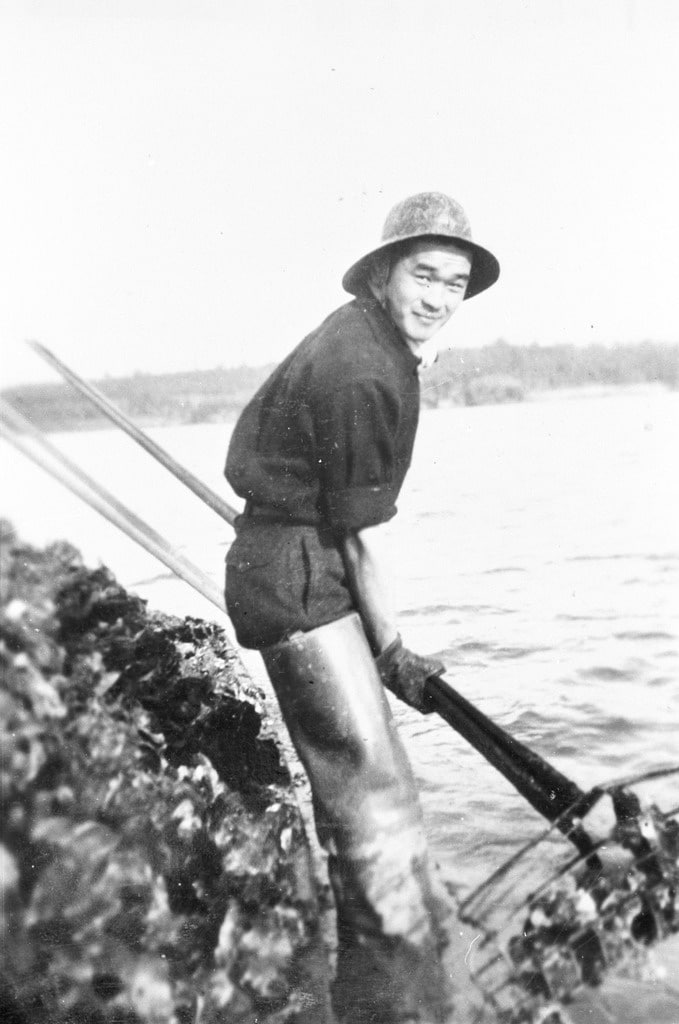

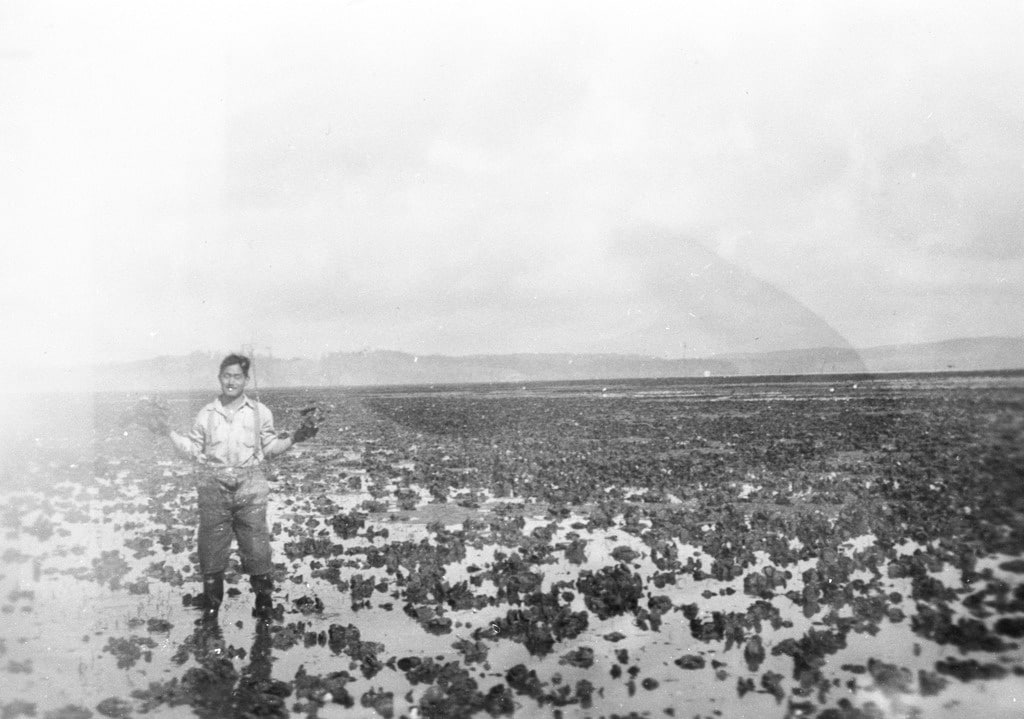

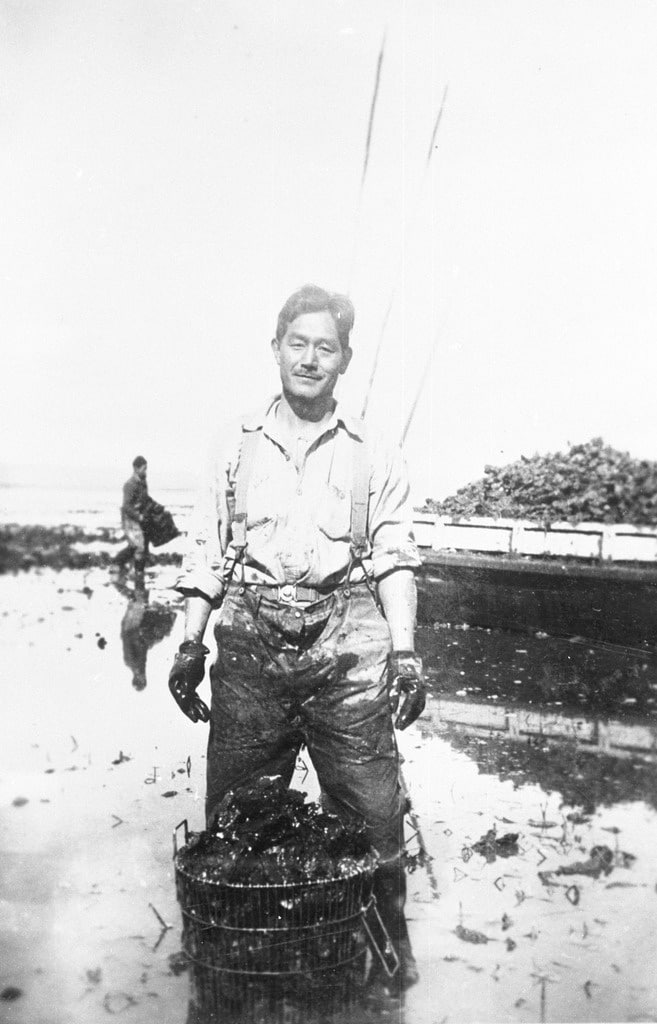

As Washington’s oyster industry grew, so did its need for a reliable labor force to help with the often-grueling work of harvesting and shucking the oysters. Japanese immigrants began arriving in the late 19th and early 20th century and made substantial contributions as part of that labor force. There are many examples of these immigrants playing important roles in the industry—despite setbacks and challenges such as the Alien Land Act of 1921.

Initially, Native Americans were employed by oyster companies to help with harvesting. Around the 1860s, Chinese immigrants began arriving in Seattle, which brought another pool of workers for a range of burgeoning industries, oysters among them. In 1882, the passage of the federal Chinese Exclusion Act suspended the immigration of Chinese laborers, taking a toll on the local labor force.

Around this time, Japanese immigrants began arriving in the Seattle area, which proved to be a great advantage for oyster businesses. Not only did these new arrivals help fill the gap left by diminishing numbers of Chinese laborers, some immigrants from Japan also had knowledge about oyster cultivation, if not direct experience with Japan’s oyster industry. In time, the portion of oyster work done by those of Japanese descent grew steadily.

By one account, in 1900, only about 3% of those employed in the oyster industry’s three prime counties—Mason, Thurston, and Pacific—were Japanese. Ten years later, that portion had increased to 40%. The growth in the number of Japanese working in Washington’s oyster labor force continued in the following years. By the time of the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941, Washington’s oyster industry was heavily reliant on Japanese workers.

As the labor force was shifting for oyster enterprises, so was the prime focus of those businesses: the oysters themselves. The only oyster native to Washington waters is the Olympia oyster, which was prolific when white settlers first arrived in the 1800s. Around the turn of the 20th century, however, there was a decline in the numbers of Olympia oysters due to a range of factors. With increased industry in the region, water quality issues began to emerge, a key culprit being effluent from pulp and paper mills. Other contributors included occasional weather extremes, overharvest (with many shipments sent to San Francisco in the latter half of the 1800s), and natural predators.

When it became clear that native Olympia oysters were in decline, some oyster growers began shipping in Eastern oysters to be grown in local beds, hoping this other American native species would do well here. A severe die-off of the Eastern species in the late 1910s put an end to hopes this oyster would make up for losses felt with the decreased harvest of Olympias.

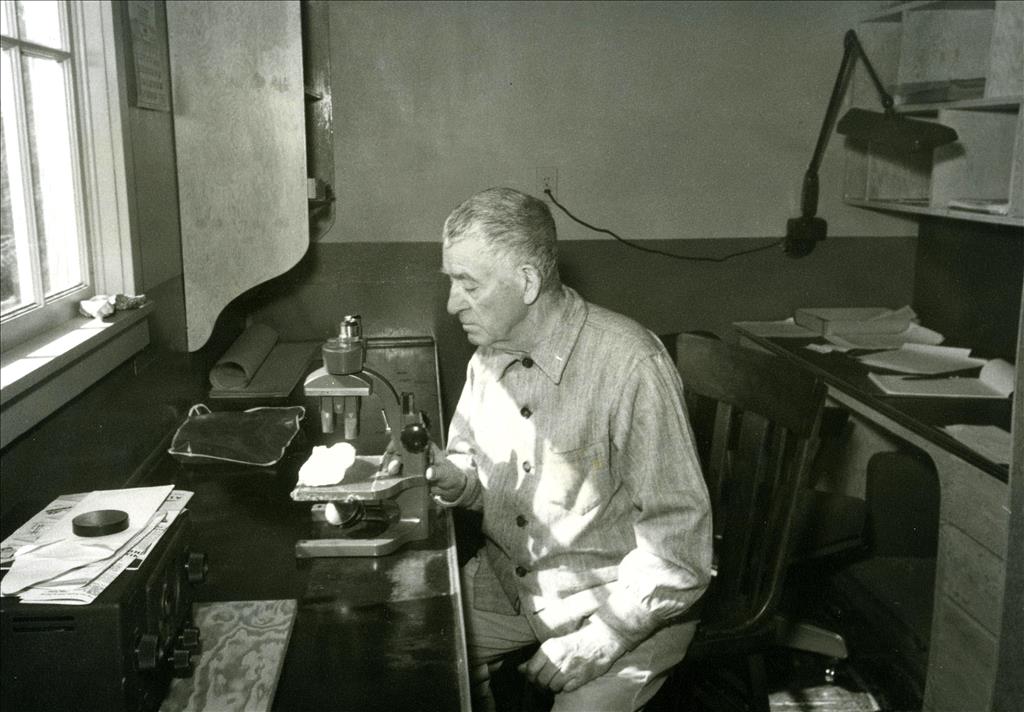

In 1912, a Japanese professor of zoology from Tokyo visited his colleague Trevor Kincaid at the University of Washington. As reported in a Seattle Daily Times item about the occasion, the visiting professor asserted that “the Japanese oysters were better adapted to the Pacific Coast of this country for transplanting than were American oysters from the Atlantic coast.” He went on to declare that “he believed the oyster trade between Japan and America was destined to grow greatly in the next decade.”

A number of trial shipments of oysters from Japan took place in the first two decades of the 20th century. Unfortunately, none of these did much to advance the interests of scientists and oystermen eager to help Japan’s native oyster find a new home in Washington. These test shipments generally experienced significant or total loss of the oysters en route.

Things changed with one particular shipment that left Yokohama in April 1919: 400 cases of oysters harvested from the Miyagi Prefecture with a final destination of Samish Bay in Washington. As recounted in Heaven on the Half Shell: The Story of the Oyster in the Pacific Northwest (Second Edition), “These fine specimens were loaded onto the deck of an American steamship, the President McKinley, covered with a protective layer of Japanese matting and given frequent showers of seawater to keep them fresh throughout the voyage.” Despite this diligence, it appeared the oysters had met with the same fate as had those in prior shipments. There was evidence of significant loss of the oysters by the time they arrived at the Pearl Oyster Company on Samish Bay. With very little expectation of success, the oysters that hadn’t perished were scattered on the beds to see if any might revive and thrive. The mature oysters, alas, did not. What they discovered within a couple of months, however, was that tiny spat—baby oysters—had gone unnoticed attached to the shells of the mature oysters. These babies were indeed alive and growing in their new home.

The Pearl Oyster Company had recently been established by J. Emy Tsukimoto and Joe Miyagi, along with six partners. This successful oyster order was among the first actions for the new enterprise. Tsukimoto and Miyagi had attended high school in Olympia, and both had worked in the local oyster industry. As had others, they sensed that the oyster from their native Japan might adapt well to the waters of their new home. They diligently studied potential locations in Washington’s oyster-friendly habitat, ultimately deciding on a plot of 600 tideland acres on Samish Bay.

With the discovery of baby oysters growing on those shells came a shift in understanding about how to best transport oysters intended for transplant to Washington beds. As oysterman and industry leader E.N. Steele wrote of this shipment in his 1964 book The Immigrant Oyster, “And so this industry was born. Little did either the oysters or those who participated in the activities know or even dream of the extent to which the industry would grow.” This new-to-Washington oyster not only proved to be a temporary relief for diminishing harvests of native Olympias and failed transplants of Eastern oysters, before long it would become the dominant oyster species harvested in Washington—a status it still enjoys today.

Within a couple of years of that first successful shipment, the societal environment became less welcoming to Japanese immigrants living in Washington. In 1921, the state’s governor Louis Hart signed into law the Alien Land Act which prohibited ownership and leasing of land by non-white aliens. Though the language of the act didn’t state as such, there was a general understanding that the legislation had Japanese farmers in mind. There was increasing concern in the agricultural community that the success of Japanese immigrants—who produced about three-quarters of the vegetables and half of the dairy products consumed in King County by 1920—was becoming a threat. The impact of this legislation was clearly felt, too, by Japanese who owned tidelands where oysters were grown. This development proved discouraging enough to Tsukimoto and Miyagi that in 1923 they sold the tidelands and their company to E.N. Steele and his business partner J.C. Barnes, who renamed the company Rock Point Oyster Company.

Shortly after the company’s sale, Tsukimoto returned to Japan where he would go on to help in supplying seed oysters to Steele and other oyster growers in Washington. Miyagi, too, returned to Japan where he apparently worked solely in Japan’s domestic oyster cultivation. Though the 1921 legislation significantly impeded the Japanese who owned tidelands for cultivation of oysters, many Japanese remained in the labor force on which the industry continued to rely.

Other Japanese immigrants who made an impact on the state’s early oyster industry include the Murakami family, who were among the first to bring Pacific oyster seed to Willapa Bay, and the Yoshihara family, who founded the West Coast Oyster Company in Mason County. Masahide Yamashita was another major player, arriving in Seattle in 1900 and trying his hand at a number of ventures before landing on the import of seed oysters from Japan, which he began around 1930. He helped form a cooperative of growers in Japan to supply seed oysters to growers in Washington, spurring the state’s expanding oyster industry.

The bombing of Pearl Harbor in December 1941 caused significant upheaval to this industry. In short order, shipments of seed oysters from Japan on which many growers had come to rely stopped. A few months later, in response to Executive Order 9066 from President Franklin Roosevelt, Washington residents of Japanese descent were forced to leave their homes and businesses and were sent to internment camps. As one item in The Seattle Times in early March 1942 noted, “Washington’s oyster industry, which produces 90 percent of the oysters on the Pacific Coast, is headed for difficult times as a result of impending evacuation of Japanese, oystermen predicted today.” The article later noted that Japanese workers represented “virtually all” of the work force for the industry at that time.

It was a challenging chapter of history, particularly so for those uprooted from their homes, their livelihoods, and their communities. As for the oyster industry in Washington, this era resulted in the loss of a large percentage of skilled and dedicated workers. Some Japanese who had been part of the strong growth of the oyster industry in the early 20th century would later return to pick up the pieces and carry on with the cultivation of oysters. Others would not. A new chapter would begin in the post-World War II years, one that would see the industry adapting and evolving in response to a wide range of opportunities and challenges. Contributions made by Japanese immigrants many years past remain part of the story today.