By Kristy Conrad, Washington Trust Development Director.

Image above: The hull of the Schooner Equator inside a shelter built by the Port of Everett.

The Equator didn’t start out as a ghoulish tale. The pygmy schooner was built in 1888 in San Francisco by California shipwright Matthew Turner. Hailed as “the ‘grandaddy’ of big-time wooden shipbuilding on the Pacific Coast,” Turner reportedly built more sailing vessels than any other single shipbuilder in America—228 seagoing vessels across 37 years, from 1868 to his death in 1905. The Equator was just one of the 133 two-masted schooners Turner built in his lifetime.

Given Turner’s business interests in the South Seas, the Equator was originally built as a copra (coconut) trading ship. A year after its launch, in March 1889, it sailed through and survived the South Pacific tropical cyclone that destroyed American and German warships and numerous merchantmen at Samoa.

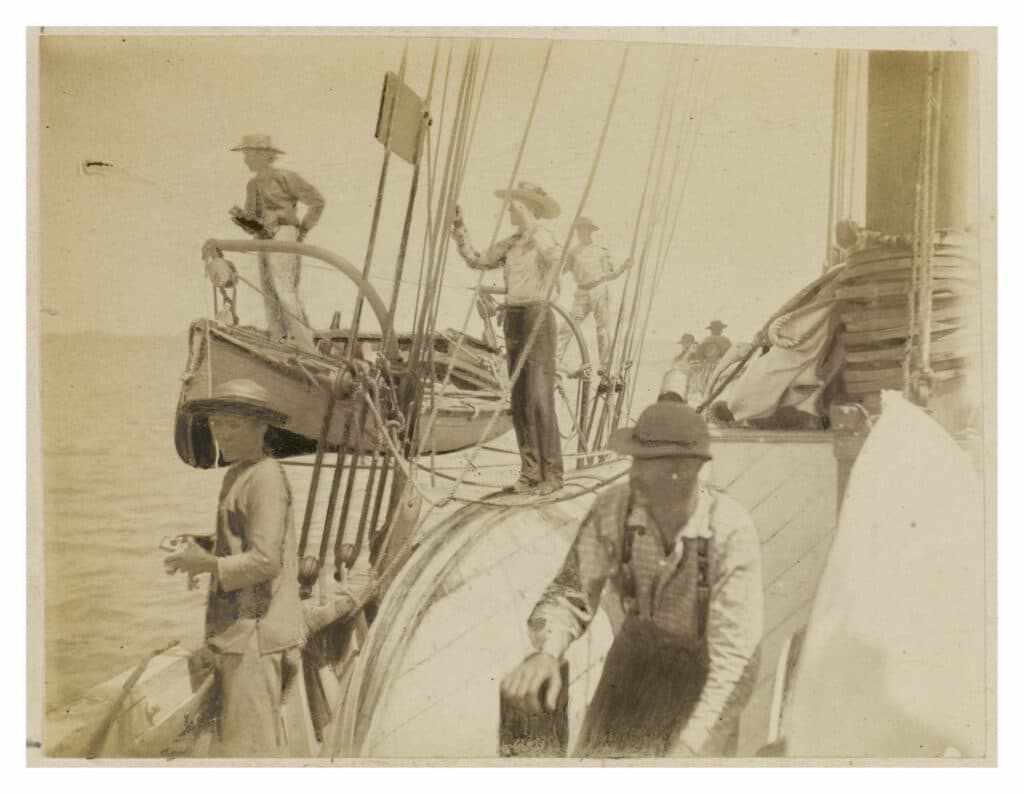

Later that year, the Equator was chartered by Robert Louis Stevenson, author of Treasure Island and Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, who sailed with his wife Fanny Vandegrift Stevenson from Honolulu to the Gilbert Islands. The voyage became the basis for Stevenson’s travelogue In the South Seas.

The Equator was equipped with a steam engine in the 1890s and worked as a tender, or support ship, for salmon cannery operations in Alaska. In 1915, the Equator arrived in Seattle, when it was purchased by the Cary-Davis Tug and Barge Company for use as a tugboat. In 1916, it was chartered by the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey to conduct coastal surveying in Alaska. Upon return, the schooner remained in operation as a tugboat until 1956, when it was abandoned on the coast of Jetty Island outside Everett as part of a breakwater with other discarded vessels. It remained there for 11 years.

In the 1960s, efforts to save the Equator were led by Everett dentist Eldon Schalka, who in 1967 mobilized volunteers from the Everett Kiwanis Club to haul the vessel ashore and clean the muck out of it. The Equator was then dry-docked at the 14th Street Fisherman’s Boat Shop in Everett. Schalka helped to establish a nonprofit group to restore the vessel, which despite little fundraising success managed to get the Equator listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1972—Everett’s first National Register listing.

Across the subsequent decades, various plans to preserve and house the Equator were proposed and fell through, and the funds necessary for a full restoration were never acquired. Reduced to a hull, the vessel was moved in 1980 to the Port of Everett’s Marina Village and later to the corner of 10th Street and Craftsman Way. In November 2017, the back of the Equator collapsed. While the port took steps to enclose the shelter around the schooner to protect it from further decay, given the extreme deterioration of the vessel, preservation in place was not an option. Left to its ghosts, the Equator was said to be visited by dancing lights above the hull at night, and psychics reported that those lights were the ghosts of Robert Louis Stevenson and his friend, Hawaiian King Kalakaua.

Sadly, those ghosts will have to find a new home. Due to its advanced state of deterioration, the schooner is to be dismantled. Still, the Port of Everett hopes to honor its legacy. “Of course, wooden vessels weren’t expected to live forever. We’re at the point where we want to make sure her legacy lives on and her story can be told,” said Port of Everett spokesperson Catherine Soper.

In June 2023, the Port partnered with a team of archaeologists from Texas A&M University to continue that story. The team spent weeks measuring every inch of the vessel to find out more about how ships were built and used in the 19th century. Because the Equator is already falling apart, the researchers were able to see its bones. “This is amazing information for us,” said Katie Custer-Bojakowski, a nautical archaeologist at Texas A&M. “We can see the framing system. That’s the backbone of the ship.” Because the research is being conducted by a public university, the data they record will be open to the public once published. “This is a form of preservation, forever,” Professor Piotr Bojakowski said.

In addition to that research, the Port of Everett has other plans to honor the Equator’s legacy. Some of the ship’s timbers are slated to be used in public art installations along the waterfront. The Port is also planning to build an interpretive exhibit with a model of the Equator at the Waterfront Center and a ship-themed playground at Jetty Landing near the 10th Street boat launch.