by Erich R. Ebel, author.

Editor’s note: In spring 2023, local authors Erich Ebel and Chuck Fowler published a new travel guide to Washington’s coastline, including many exciting locations within the Maritime Washington National Heritage Area. To celebrate this new book, Erich Ebel shares some of his experiences and favorite locations from Exploring Maritime Washington.

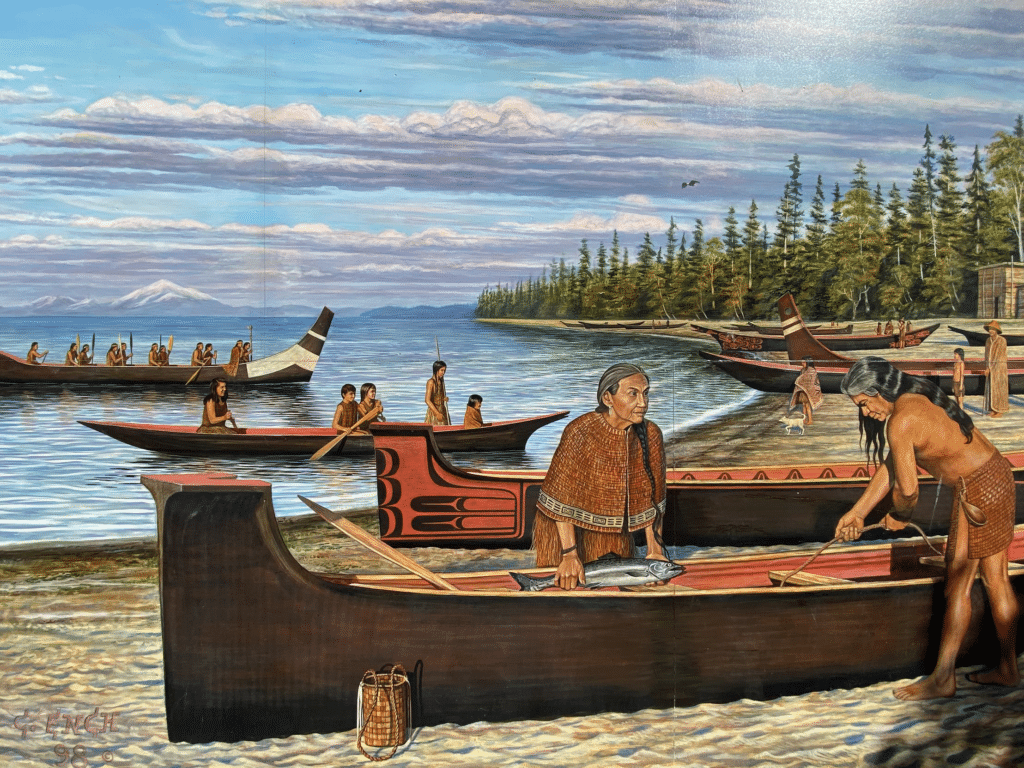

My hope is that by writing Exploring Maritime Washington, we have provided the casual Washingtonian with a handbook through which they can discover new and fascinating details about our common nautical heritage. Whether first experienced by the continent’s Indigenous peoples or by the explorers who came much later, the immigrant fishermen who made their living by the sea or the stevedores who have kept our state’s economy vibrant by the sweat of their labor, the history we share today is one of the strongest common threads that binds us together as a society.

The very first words I wrote in the book’s acknowledgements section are these: “It would be impossible to fit the entirety of Washington’s maritime history into a book of this size.” That is an absolute fact, and winnowing the vast number of stories was a grueling, emotionally draining exercise. The bad news is that some stories simply had to go untold in Exploring Maritime Washington, not because their quality was lacking or their value to state history was insignificant, but because publishers have content limitations and not every story (though fascinating in its own right) had a direct maritime connection. The good news is that I saved everything that didn’t make the cut to include in future books about Washington state history, heritage, and culture. Those stories will also be told.

One of my favorite stories from the book comes from the Makah Tribe on the Olympic Peninsula. Hundreds of years ago, their society consisted of five main villages—Osett, Dia’th, Wa’atch, Tsoo-yess, and Ba’adah. Sometime between the 1500s and 1700s, Makah residents of Osett (known now as Ozette) were going about their daily lives when a rain-soaked hillside suddenly broke loose and buried the village under feet of mud and debris. Generation after generation passed until the 1970s when a fierce storm finally began revealing what nature had wiped out centuries earlier. The Makah then partnered with archaeologists from Washington State University to begin painstakingly uncovering the remains of their once-vibrant village. Near the site today is a small, weathered longhouse constructed by the Makah Tribe as a memorial to their ancestors who lost their lives in the mudslide. Within the structure itself is an oxidized bronze plaque describing how the tragedy has given rise to a new understanding for the Makah people. Through the archaeological study of the site, their people have gained a greater appreciation of the wisdom of their forefathers and a renewal of their desire to strengthen their culture.

Although not within the Maritime Washington National Heritage Area, another oft-overlooked heritage site that has captured a special place in my heart is the Knappton Cove Heritage Center on the Columbia River, a small, unassuming building with a wooden sign reading “U.S. Quarantine Station, 1899-1938” that should cause any traveler to pause long enough to wonder about the history of such a place. Indulging in that curiosity, in this case, will be well rewarded given that it once bore the nickname “The Ellis Island of the Pacific.” The site was one of many hospitals and health facilities operated by the U.S. Public Health Service during the country’s foundational period. In its first year of operation, staff inspected 6,120 immigrants and crewmen passing through the Columbia River. For nearly 40 years, European and Asian immigrants suffering from the bubonic plague, yellow fever, cholera, smallpox, typhus, and other maladies passed through health inspection at this facility. By the time it closed in 1938, approximately 100,000 immigrants and crew had been run through the quarantine station. The waters in front of the property today still reveal hundreds of foundational pilings at low tide—remnants of the past that leave a footprint of what once was considered a shield for the Columbia River.

There are dozens of additional maritime heritage sites to be found within the pages of Exploring Maritime Washington, which is available now through Amazon, The History Press, or your local bookstore (if they don’t carry it yet, ask them to order some!). This historical travel guidebook seeks to provide Washington residents as well as visitors from near and far with a more comprehensive, inclusive picture and understanding of the maritime heritage of Washington. The uniqueness of Exploring Maritime Washington is based on providing the history enthusiast and travelers a hands-on guide to the state’s myriad cross-cultural attractions, sites, and stories. By visiting and experiencing Washington’s special maritime features—museums, ships, lighthouses, waterfronts, and all—the heritage traveler can obtain an authentic understanding of maritime Washington’s diverse, inclusive history and culture.